Menu

Be careful what you comment -- it might get you sued

|

|

You have a bad experience with a product or service and decide to share your negative impression with the world via an anonymous comment posted on a popular online retailer. The company you criticized responds to the comment by threatening you with legal action. Should you shrug it off or contact your attorney? The answer is not so clear-cut these days.

|

According to a July 17, 2014, article by David Kravets on Ars Technica, the company could win a court order demanding that the retailer reveal your identity:

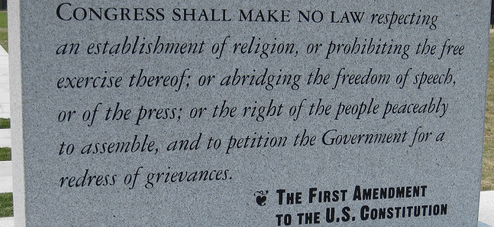

"Ubervita, a Washington state company that sells testosterone boosters, multivitamins, and weight loss supplements, has been responding in the comments section under its products to blast those leaving negative reviews... [calling the comments] libel and defamation.... 'You should probably stop before you get into a lot of legal trouble,' a rep for the company commented to a reviewer on Amazon.com." Kravets reports that Ubervita's comments were subsequently removed, but he links to a PDF that captured them. Ubervita sued for and won the right to demand Amazon reveal the identity of the commenters. The judge ruled: "Ubervita may serve subpoenas on Amazon, Inc. (or other appropriate Amazon entity) and Craigslist, Inc. (or other Craigslist entity) intended to learn the John Doe defendants’ identities, including their names, addresses, telephone numbers, e-mail addresses, IP addresses, Web hosts, credit card information, bank account information, and any other identifying information." Public Citizen attorney Paul Alan Levy worked with Ubervita's lawyers to limit the scope of the subpoenas to determine only whether the posts were by employees or agents of the company's competitors, which protected the "larger group of Ubervita critics," according to Levy. A pseudonym is no protection against true defamation The other side of the comments-as-defamation coin is a case reported on the JDSupra site on July 17, 2014, by Richard Raysman, an attorney for Holland & Knight, LLP. In Judge v. Randell,[1] a contractor (Greg Judge) sued to determine whether a former client (Lori Randell) created a fake identity that was used to post negative online reviews about the contractor. After the two disputed an oral contract for home-improvement work, Jerry Glassman, who had previously claimed to be Randell's attorney, wrote on various sites that Judge was drunk on the job, in addition to being "inethical [and] untrustworthy," according to Raysman. Judge claimed Randell actually wrote the posts attributed to Glassman (the "pseudonym theory"), but the court ruled that Judge failed to provide evidence sufficient to prove Randell wrote the posts using Glassman's name. However, the court found that Glassman may have been acting as Randell's agent, which would make Randell liable as a principal who approved Glassman's defamatory postings (the "agency theory"). The appellate court upheld the trial court's ruling on the agency theory and also found that Judge offered enough evidence to show Randell and Glassman may have been one person, or that Randell wrote the reviews under Glassman's name, so the pseudonym theory also had merit. In addition, the appellate court identified two statements in the posts that a trier of fact could find to be false, as required by a defamation claim. If it's on the Internet, it's assumed to be opinion, not fact A defense to a charge of defamation is that you were merely expressing an opinion, not making a statement of fact. Opinion is protected as free speech under the First Amendment. A July 16, 2014, article on JDSupra written by Raysman describes a recent New York state court decision that found material on the Internet is presumed to be opinion rather than a statement of fact. In Nanoviricides, Inc. v. Seeking Alpha, Inc.[2], a pharmaceutical company (Nanoviricides) sued a "bulletin board" that offered investment and financial advice after someone using a pseudonym posted negative comments about Nanoviricides, which researches and develops anti-viral drugs. Nanoviricides claimed the statements were defamatory: they were false and subjected the company to "public contempt, ridicule or disgrace." Courts use a four-part test to determine whether a statement is an assertion of fact: first, "whether the statement has a precise meaning so as to give rise to clear factual implications"; second, "the degree to which the statements are verifiable"; third, "whether the full context of the communication in which the statement appears signals to the reader is nature as opinion"; and fourth, "whether the broader context of the communication so signals the reader."[3] The court ruled that the post was opinion because the article in question included a disclaimer stating that the content was "the author's own opinion," and the author's assertions were backed up by facts, including a link to a complaint that had been filed against Nanoviricides by a shareholder alleging malfeasance. Also arguing in favor of opinion rather than assertion of fact was the medium used to convey the message. The decision states that the Internet is "often the repository of a wide range of casual, emotive, and imprecise speech." Was the court stating that everything on the Internet is presumed to be opinion rather than a statement of fact? I'll drink to that! [1] No. A138481 (Cal. Ct. App. July 7, 2014). [2] No. 151908/2014, 2014 NY Slip Op 31681(U) (N.Y. Sup. Ct., N.Y. Co. June 26, 2014). [3] Sandals Resorts Int'l Ltd. v. Google, Inc., 86 A.D.3d 32, 39-40 (N.Y. App. Div. 2011). |