Menu

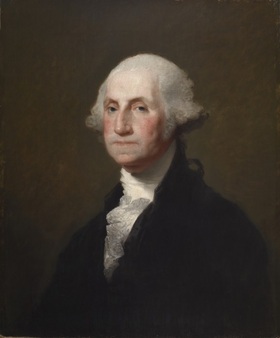

What would George Washington think of his country now?

Who exactly are we celebrating today? February 22 used to be the day we honored George Washington on his birthday, just as we feted Abraham Lincoln on the anniversary of his birth on February 12, 1809 -- at least we did so in most states.

According to History.com, Washington's Birthday was one of the first five national holidays, designated as such by Congress in 1885. The others were Christmas Day, New Year's Day, Independence Day, and Thanksgiving. In 1971, the Uniform Monday Holiday Act moved Washington's Birthday to the third Monday in February. Memorial Day, Columbus Day, and Veterans Day were also changed from their traditional dates of May 31, October 12, and November 11, respectively, although in 1980 Veterans Day was moved back to its original date.

It was actually marketers who started calling the February holiday Presidents Day, starting in the 1980s. Nearly all states have changed the holiday's official designation to Presidents Day, but the federal government continues to refer to it as Washington's Birthday. (Note that Lincoln's Birthday has never been recognized as a federal holiday, although many states had done so prior to the creation of Presidents Day, which is generally perceived as honoring Washington and Lincoln primarily.)

George Washington is one of those rare icons who actually deserve the accolades. The Colonial rebels were definite longshots when the Revolutionary War began. Many factors contributed to their ultimate victory, including the French seeking payback for their loss of the Seven Years War, and the Prussian-born General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben playing a key role in transforming a ragtag bunch of farmers, tradesmen, and laborers into an army.

Still, Washington's triumphs as a military leader are topped by his accomplishments as a political leader. He supervised the creation of the federal government. He asserted the federal government's supremacy over the states in fighting the Whiskey Rebellion. He assured the country's westward expansion by setting lose General "Mad Anthony" Wayne on the British-backed Native American tribes in what were then the Northwest Territories (the evils of such manifest destiny, particularly from the Native American perspective, are duly noted). Washington also established the policy of neutrality to avoid "foreign entanglements."

But one of Washington's greatest gifts to Americans is his Farewell Address, which was actually an open letter to citizens present and future. We would do well to dust off this historic document each year as a reminder of the legacy we've been entrusted with. Our first and (arguably) greatest President offered the address as "the disinterested warnings of a parting friend."

If we are not one, we are nothing

Washington ties everything we have and everything we hope for to a single principle: "unity of Government, which constitutes you one people." He instructs us to trust the Constitution, which the people have a right and obligation to amend when necessary, but which "is sacredly obligatory upon all."

Washington rails against factions that attempt "to put, in the place of the delegated will of the nation, the will of a party, often a small but artful and enterprising minority of the community" whose ultimate goal is "to make the public administration the mirror of the ill-concerted and incongruous projects of faction." Despite their popularity, any such factions are destined ultimately "to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people, and to usurp for themselves the reins of government; destroying afterwards the very engines, which have lifted them to unjust dominion."

Much of Washington's address is a caution against the "baneful effects of the spirit of party," claiming it is "the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it." A free government requires morality born of religion, according to Washington, and "the general diffusion of knowledge" to ensure "enlightened" public opinion. He points out that public debt is inevitable to preserve liberty, but it should be minimized.

"Observe justice and good faith to all nations," he instructs us, and bear animosity toward none. Nor should we favor any one nation over others to avoid introducing foreign influence that misleads public opinion. Foreign entanglements have proven impossible for the United States to avoid, but the struggle goes on to minimize if not outright prevent foreign influence on our internal affairs.

Washington's advice in a nutshell: Avoid party factions and foreign entanglements. Are we listening? If not, why not?

According to History.com, Washington's Birthday was one of the first five national holidays, designated as such by Congress in 1885. The others were Christmas Day, New Year's Day, Independence Day, and Thanksgiving. In 1971, the Uniform Monday Holiday Act moved Washington's Birthday to the third Monday in February. Memorial Day, Columbus Day, and Veterans Day were also changed from their traditional dates of May 31, October 12, and November 11, respectively, although in 1980 Veterans Day was moved back to its original date.

It was actually marketers who started calling the February holiday Presidents Day, starting in the 1980s. Nearly all states have changed the holiday's official designation to Presidents Day, but the federal government continues to refer to it as Washington's Birthday. (Note that Lincoln's Birthday has never been recognized as a federal holiday, although many states had done so prior to the creation of Presidents Day, which is generally perceived as honoring Washington and Lincoln primarily.)

George Washington is one of those rare icons who actually deserve the accolades. The Colonial rebels were definite longshots when the Revolutionary War began. Many factors contributed to their ultimate victory, including the French seeking payback for their loss of the Seven Years War, and the Prussian-born General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben playing a key role in transforming a ragtag bunch of farmers, tradesmen, and laborers into an army.

Still, Washington's triumphs as a military leader are topped by his accomplishments as a political leader. He supervised the creation of the federal government. He asserted the federal government's supremacy over the states in fighting the Whiskey Rebellion. He assured the country's westward expansion by setting lose General "Mad Anthony" Wayne on the British-backed Native American tribes in what were then the Northwest Territories (the evils of such manifest destiny, particularly from the Native American perspective, are duly noted). Washington also established the policy of neutrality to avoid "foreign entanglements."

But one of Washington's greatest gifts to Americans is his Farewell Address, which was actually an open letter to citizens present and future. We would do well to dust off this historic document each year as a reminder of the legacy we've been entrusted with. Our first and (arguably) greatest President offered the address as "the disinterested warnings of a parting friend."

If we are not one, we are nothing

Washington ties everything we have and everything we hope for to a single principle: "unity of Government, which constitutes you one people." He instructs us to trust the Constitution, which the people have a right and obligation to amend when necessary, but which "is sacredly obligatory upon all."

Washington rails against factions that attempt "to put, in the place of the delegated will of the nation, the will of a party, often a small but artful and enterprising minority of the community" whose ultimate goal is "to make the public administration the mirror of the ill-concerted and incongruous projects of faction." Despite their popularity, any such factions are destined ultimately "to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people, and to usurp for themselves the reins of government; destroying afterwards the very engines, which have lifted them to unjust dominion."

Much of Washington's address is a caution against the "baneful effects of the spirit of party," claiming it is "the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it." A free government requires morality born of religion, according to Washington, and "the general diffusion of knowledge" to ensure "enlightened" public opinion. He points out that public debt is inevitable to preserve liberty, but it should be minimized.

"Observe justice and good faith to all nations," he instructs us, and bear animosity toward none. Nor should we favor any one nation over others to avoid introducing foreign influence that misleads public opinion. Foreign entanglements have proven impossible for the United States to avoid, but the struggle goes on to minimize if not outright prevent foreign influence on our internal affairs.

Washington's advice in a nutshell: Avoid party factions and foreign entanglements. Are we listening? If not, why not?