Menu

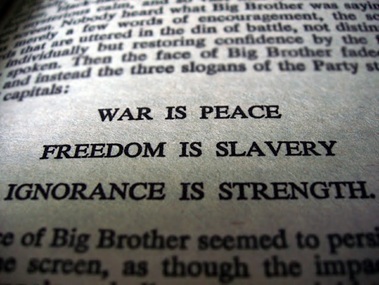

Silly questions: Who ‘owns’ video captured by police? And does Facebook really ‘enhance’ privacy? |

“Mr. Khan… has no right to stand in front of millions of people and claim I have never read the Constitution.” Classic doublespeak, even for a master like the Republican nominee for the 2016 Presidential election. His “defense” actually proves his opponent’s point. It’s right there in the First Amendment: “Congress shall make no law… abridging the freedom of speech.” So Khizr Khan does indeed have the Constitutional right to claim that the Republican nominee has never read the Constitution. But then again, how would the nominee ever know that, considering he’s as clueless about the Constitution as he is about every other aspect of our democratic form of government? I recently came across a telling example of a public official’s arrogance on display via her own words. The District Attorney of Sonoma County, Jill Ravitch, is under pressure for refusing to release to defense attorneys the video from the body cameras worn by certain law-enforcement officers that relate directly to the cases of the defense attorneys’ clients. In defending her refusal to release the videos without stringent requirements imposed on the opposition attorneys beforehand, Ravitch wrote in a July 17, 2016, op-ed column in the Santa Rosa Press Democrat that “[the body-cam video] legally belongs to the law enforcement agency that conducted the investigation.” According to Ms. Ravitch, the local police legally own the video they capture with cameras purchased with public funds. When the city of Gardena, California, refused to release police video of a shooting by officers of the department, a U.S. District Court judge ordered the video released because the city had paid a settlement to the victim’s family. Therefore, the court ruled, the citizens had a right to know how and why their money was spent. The Los Angeles Times’ Richard Winton writes in a July 29, 2015, article that the city signed the $4.7 million agreement with the understanding that the videos would remain sealed. An issue is whether the city had the authority to deny the public the right to view the video in question. The best you can say is that the issue of who “owns” video captured by police officers on duty remains unsettled. Legal underpinnings of 'government ownership' of information The way to assert ownership of a published material is by copyright. Yet the Copyright Act of 1976, which is codified as title 17 of the United States Code (pdf), states that “No copyright shall subsist ... in any publication of the United States Government, or any reprint, in whole or in part, thereof.” (17 USC § 8, also section 105 of the Copyright Act of 1976). While the U.S. Code applies only to federal government agencies, California is one of several states that have passed laws placing all government works in the public domain. The Copyright Office also considers “edicts of government,” including “judicial opinions, administrative rulings, legislative enactments, public ordinances, and similar official legal documents, not copyrightable for reasons of public policy,” according to Wikipedia. This rule applies to local, state, federal, and foreign governments. North Carolina’s legislature recently passed a law scheduled to take effect in October that allows the police to refuse to release any video captured by police for any number of spurious reasons. According to a July 11, 2016, article by Lynn Bonner of the News & Observer, a police chief or sheriff can simply decide that disclosure might harm someone’s reputation or jeopardize their safety. The catchall excuse for withholding the video states that the government agency may do so if confidentiality is “necessary to protect either an active or inactive internal or criminal investigation or potential internal or criminal investigation.” Vague much? To start with, when does the window close on a “potential” internal or criminal investigation? The police can hold onto the video for any reason, for as long as they wish, short of a court order to release it. Thus a tool intended to improve the transparency of government serves instead to obfuscate government operations more than they are already. To end with (and skipping all the unreasonable stuff in between), this policy gives prosecutors even more power than they wielded previously, at the expense of the defense. (The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press provides an interactive map of police departments that supply their officers with bodycams, and their policies for releasing the resulting videos.) One state takes a safe-and-sane approach to release of police bodycam video New Hampshire’s law on release of police bodycam video requires police departments to retain video depicting “contentious events” for at least three years, according to Bloomberg’s Joshua Brustein in a July 13, 2016, article. Those events include any use of force by police, or an encounter that leads to a citizen complaint against an officer. A person seeking release of the video must file a “legitimate” public-records request, according to the regulation, which was signed into law by New Hampshire Governor Maggie Hassan on June 28, 2016. The New Hampshire law also prevents disclosure of police bodycam videos that don’t depict police use of force or potential abuse of police power, and all videos that aren’t in either category must be erased within 180 days of their original recording. This is intended to prevent blanket requests such as those made by activists in Seattle, who subsequently posted the police videos on YouTube. The New Hampshire approach seems to be a good compromise between the public’s right to access video depicting potential police abuse, and the privacy rights of the people depicted in the videos, including police officers. Requests must state with particularity which video is being sought, and the legitimate reason for the request. The people will be best served by policies governing videos captured by police that balance the need for transparency in law enforcement with the need to protect the privacy of all citizens, public and private alike. Giving prosecutors unfettered discretion to release or not to release the videos serves no one. ---------------------------------------------------------------- Facebook: Paragon of privacy Want a classic example of doublespeak, private-sector style? How about Facebook VP of Public Policy Erin Egan insisting the company is now the model of privacy protection in the digital age? In a July 30, 2016, interview with the Daily Dot’s Aaron Senkins – conducted, of all places, at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland – Egan asserts that Facebook is a “privacy-enhancing platform.” Evidently, she said this with a straight face. A service that collects, stores, shares, and otherwise reuses your personal photographs and the details of your day-to-day life enhances your privacy? A service that knows who and what you like and dislike, and who and what likes and dislikes you, makes you more private than you were before you ever heard of Facebook? Um, no. Facebook makes you more private in absolutely no way. None. Not one. (The June 2, 2015, Weekly presented a five-minute Facebook security checkup, and the September 8, 2015, Weekly described three simple ways to improve your privacy, the first of which is to see your Facebook profile the way the public sees it.) Egan admits Facebook users are confused about how to control what they share and who they share it with, but she states that it’s the responsibility of users to educate themselves on the many privacy-robbing options available to them on Facebook. In 2010, Mark Zuckerberg told the audience at the TechCrunch awards that the age of privacy was over. That was about the same time the service unilaterally changed all Facebook accounts to “public,” even if their owners had chosen to keep their profiles private. In 2014, after much pressure from government agencies and privacy-loving users, Facebook reverted and made private profiles the default for all new users. In Facebook-speak, their profiles and timelines are accessible only to their friends, and in some cases their friends of friends. In an April 7, 2016, article, Fortune’s Erin Griffith writes that the number of personal posts on Facebook has declined by 21 percent, according to the company’s own figures. Griffith attributes the drop in personal sharing to the increase in professional content on Facebook, as well as on users becoming more aware of their lack of privacy when using the service. As Griffith states, Facebook’s privacy settings are too complicated, so people don’t even bother with them and instead self-censor. People also realize that even with a “private” profile, they have no control over how widely the information they post on Facebook will be shared. Griffith writes that intimacy is what makes Facebook a success, but intimacy is precisely what Facebook is losing as users realize the service is in fact a very public place. Could privacy turn out to be Facebook’s Achilles heel? At the least, it creates an opportunity for all those Davids out there to take a crack at Goliath. ------------------------------------------------------------------ How do they track thee, let us count the ways… (To the tune of Bob Dylan’s “Everybody Must Get Stoned”:) They track you when you’re driving in your car. They track you when you’re texting in a bar. They track you when you walk into a store. They track you when step outside your door. In this modern world of ours, it’s a fact: Everybody must get tracked. In his June 27, 2016, article, Tech Insider’s Kevin Kelly came up with 24 ways our activities are recorded, with or without our knowledge. If your car is model year 2006 or later, it has a chip embedded that records your speed, braking, turns, mileage, and accidents. Each month, 70 million license plates are scanned using sensors and cameras mounted on poles near highways. That figure doesn’t include the license-plate scanning done by nearly every police patrol vehicle on the road. All travel itineraries for air and train trips are recorded. Every piece of mail you send and receive is scanned and saved. Where, when, and who you call on your cell phone is recorded, and some services capture and retain the contents of calls and voice messages for years. Sixty-eight percent of public employers and 59 percent of private employers video-record their workplaces, as do 98 percent of banks, 64 percent of public schools, and 16 percent of homeowners. Credit-card companies mine data related to your purchases to devise profiles that reveal “your personality, ethnicity, idiosyncrasies, politics, and preferences,” according to Kelly. The movies you watch on Netflix, the music you listen to on Spotify, and the videos you view on YouTube are all carefully recorded. Same as the books you buy on Amazon or check out of the public library. Speaking of books, your life is an open one. ------------------------------------------------------------------- Twenty-first century version of toxic waste: Metadata Metadata is data about data. When you make a phone call, the details of the call that aren’t part of the content of your conversation are metadata: Who you called, when you called, where you were when you called, how long you talked, perhaps even what you were doing immediately before and what you do immediately after the call as well. Put all this metadata together and you get a pretty good glimpse into what the call was all about. Now multiply this by every type of digital transaction you make. That’s a lot of metadata – some of which can be hazardous to your health and wellbeing. In a July 13, 2016, article, TechCrunch’s Nico Sell and Rita Zolotova write that metadata has become “a breeding ground for the next wave of cyber risks at all levels — reputational, financial, and national security.” An entire industry has grown around mining metadata for profit. The amount of metadata generated is expected to skyrocket with the arrival of the Internet of Things, which places data-collecting sensors nearly everywhere. We don’t know what metadata is being collected about us, who is doing the collecting and mining, where the metadata is stored, how it is used, or most importantly, how to get rid of it. As a recent Stanford University study highlights, telephone metadata is particularly dangerous in terms of the potential for misuse. While it is difficult to limit the amount of metadata that is collected, it would be relatively easy to set a mandatory expiration data for the information. This is in addition to anonymizing and encrypting the data, neither of which is guaranteed to occur at present. |