Menu

Publishers are losing the battle against their ad-blocking visitors - So what's next?

Every Sunday morning, I start the day by removing the ad inserts from the newspaper and recycling them sight unseen. I’ve been doing it for decades, and no publisher has accused me of piracy or of being a member of the mafia.

I’ve been using ad-blocking browser extensions for most of the last decade to remove the ads from the sites I visit. According to the UK’s cultural secretary, John Whittingale, this makes me part of a “modern-day protection racket” that’s tantamount to piracy. Whittingdale is quoted by The Stack’s Martin Anderson in a March 2, 2016, article.

How is blocking ads on a web site or mobile phone different from tossing the advertising inserts that accompany my newspaper? I choose which portions of the newspaper to read and which not to read, just as I choose which portions of the sites I peruse I want to display and which I prefer to block. Yet when I block ads on my computer or mobile phone, I’m accused of breaching an implied contract with the publishers. Wha?

Publishers are definitely concerned about ad blockers. Randall Rothenberg, who is president and CEO of the Internet Advertising Bureau, told the audience at the group’s annual conference last January that companies offering ad-blocking products are “profiteers” who operate “an old-fashioned extortion racket.” According to Rothenberg, AdBlock Plus and other ad blockers are “subverting freedom of the press,” and he cited a German blogger who called the company a “mafia-like advertising network,” as Anderson reported in a January 26, 2016, article on The Stack.

Are we contractually obligated to view ads on sites and phone apps?

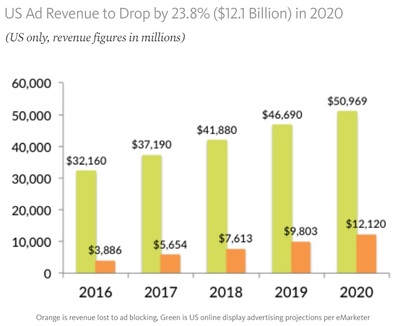

Indications are that publishers who rely on ads for their profit from online content will continue to experience revenue declines as a result of increased use of ad blockers. Juniper Research’s recent report entitled Worldwide Digital Advertising 2016 - 2020 forecasts that publishers will lose $27 billion through 2020 as a result of their readers’ use of ad-blocking tools (a different set of numbers from eMarketer is presented above, but the trends parallel). BetaNews’ Sead Fadilpasic reports in a May 12, 2016, article that the revenue lost due to blocked ads will account for 10 percent of the total digital advertising market in 2016, according to figures compiled by Statista.

Juniper’s study claims that the percentage of people who block ads will continue to climb, led by millennials, who are the group most likely to use ad blockers. Several popular sites have begun to prevent people who are using ad blockers from viewing the sites’ content until the visitors disable the blockers (Forbes.com, for example) or pay a fee (Wired.com asks for $1 a week to view the site minus ads). As The Stack’s Anderson reports in an April 21, 2016, article, such sites are paying the price for their aggressive anti-blocking strategy.

According to figures from web-traffic monitor Alexa, Wired’s global rank among the most-visited sites declined by 174 points after it implemented its anti-blocking program, falling to 853rd overall, and the site’s bounce rate increased 3 percent to 69.6 percent. Wired’s daily page views fell near 5 percent, although average time spent on the site per user was unchanged. Similarly, Forbes’ bounce rate rose 27 percent after it started its campaign against ad blockers, and page views fell close to 9 percent compared to views prior to the change. Average daily time on the site also declined by 9 percent.

The Washington Post is one of several publishers who gave blocking ad blockers a try only to back off after experiencing sharp declines in viewership, according to Anderson, who concludes that “instituting these deterrents is financially suicidal.” That sentiment is echoed by Doc Searls in a May 9, 2016, post on his blog on the Harvard University site. Searls quotes the report Interaction 2016 published by media investment firm GroupM:

Tracking and targeting intended to make advertising welcome makes it a nuisance. It is dysfunctional. The advertiser damages his reputation and pays to do so.

Even though sentiment is growing within the ad-tech community that things are going south fast – Searls quotes one ad-tech executive as referring to the industry as “a walking zombie” – other representatives of publishers and online ad networks continue their war against their own ad-blocking customers. One of their recent claims is that blocking ads breaches an implied contract between publisher and reader. In a September 25, 2015, article on Phys.org, David Glance dismantles this argument piece-by-piece.

To begin with, courts have long ruled that advertisements aren’t offers (with a small number of specific exceptions), they’re invitations to negotiate. (FindLaw offers a detailed discussion of the legal status of advertisements.) In a nutshell, a contract requires an offer, an acceptance, and bargained-for consideration. Glance points out that “visitors are never given the explicit choice to make that informed decision.”

Is visiting a site or using a free ad-supported app on your mobile phone tantamount to a contract of adhesion, which is similar to the boilerplate on the back of the ticket you take when you park your car in a commercial lot? Publishers may believe their terms of service create such a contract, but courts have ruled recently that the arbitration clauses included in such agreements are not legally binding, as Edward P. Boyle and Shahin O. Rothermel of Venable LLP explain in a May 6, 2016, post on Law360.

Also arguing against a contractual relationship between advertiser/publisher and site visitor is the fact that consumers aren’t told what exactly they are giving up in exchange for the personal data they surrender to the online ad trackers. In his Phys.org article, Glance points out that “in addition to the loss of privacy and the visual experience of ads, their data allocation is going to be used, web pages will load slower, and overall, their experience of the site will be diminished.”

For a contract to be valid, both parties must enter into it knowingly and voluntarily. How can you agree to a contract when the key terms are unknown? Consumers may know the value of what they’re getting, but they have no clue as to what exactly they are giving up in exchange, let alone having a reliable way to calculate its value.

The end of online advertising as we know it

In his Harvard blog post, Searls lists some of the many indications that the ad-tech bubble is popping. Ironically, the two companies that have profited the most from online ads – Facebook and Google – appear to be positioned to weather the transition to whatever form of online monetization comes next. Searls quotes an ad-tech executive who states that Facebook “owns the relationship with the user, and decides what content the user sees and how many see it.”

Google is reportedly working on an acceptable-ad policy similar to the one used by its nemesis, AdBlock Plus, according to Searls. At the same time, online-ad fraud seems to be on the decline. (I wrote about online-ad fraud most recently in the May 3, 2016, Weekly, as well as in the April 7, 2016, article, “More reasons why you need to block web ads.”)

Still, you should shed no tears for digital publishers or online ad networks. Nima Wedlake writes in an April 11, 2016, post on the Thomvest Ventures blog that in 2016 digital advertising will surpass TV ads for the top spot in total revenue, reaching $66 billion for the year. Mobile ad revenue is forecast to grow 30 percent annual through 2019, according to Thomvest research.

People will continue to block ads, and digital publishers will continue to make money in spite of it. It’s possible the online ad networks – and the companies that make their livelihood from them – will finally police themselves so the ads are less annoying and the tracking/data collection more transparent. (An opt-out function that boots the ads in exchange for micropayments would be a welcome addition.)

Whether the ad-tech industry can prevent itself from killing the goose that lays the golden eggs is a wide open question. For now, your best option remains to block ads while we wait for a safer and more palatable alternative.

I’ve been using ad-blocking browser extensions for most of the last decade to remove the ads from the sites I visit. According to the UK’s cultural secretary, John Whittingale, this makes me part of a “modern-day protection racket” that’s tantamount to piracy. Whittingdale is quoted by The Stack’s Martin Anderson in a March 2, 2016, article.

How is blocking ads on a web site or mobile phone different from tossing the advertising inserts that accompany my newspaper? I choose which portions of the newspaper to read and which not to read, just as I choose which portions of the sites I peruse I want to display and which I prefer to block. Yet when I block ads on my computer or mobile phone, I’m accused of breaching an implied contract with the publishers. Wha?

Publishers are definitely concerned about ad blockers. Randall Rothenberg, who is president and CEO of the Internet Advertising Bureau, told the audience at the group’s annual conference last January that companies offering ad-blocking products are “profiteers” who operate “an old-fashioned extortion racket.” According to Rothenberg, AdBlock Plus and other ad blockers are “subverting freedom of the press,” and he cited a German blogger who called the company a “mafia-like advertising network,” as Anderson reported in a January 26, 2016, article on The Stack.

Are we contractually obligated to view ads on sites and phone apps?

Indications are that publishers who rely on ads for their profit from online content will continue to experience revenue declines as a result of increased use of ad blockers. Juniper Research’s recent report entitled Worldwide Digital Advertising 2016 - 2020 forecasts that publishers will lose $27 billion through 2020 as a result of their readers’ use of ad-blocking tools (a different set of numbers from eMarketer is presented above, but the trends parallel). BetaNews’ Sead Fadilpasic reports in a May 12, 2016, article that the revenue lost due to blocked ads will account for 10 percent of the total digital advertising market in 2016, according to figures compiled by Statista.

Juniper’s study claims that the percentage of people who block ads will continue to climb, led by millennials, who are the group most likely to use ad blockers. Several popular sites have begun to prevent people who are using ad blockers from viewing the sites’ content until the visitors disable the blockers (Forbes.com, for example) or pay a fee (Wired.com asks for $1 a week to view the site minus ads). As The Stack’s Anderson reports in an April 21, 2016, article, such sites are paying the price for their aggressive anti-blocking strategy.

According to figures from web-traffic monitor Alexa, Wired’s global rank among the most-visited sites declined by 174 points after it implemented its anti-blocking program, falling to 853rd overall, and the site’s bounce rate increased 3 percent to 69.6 percent. Wired’s daily page views fell near 5 percent, although average time spent on the site per user was unchanged. Similarly, Forbes’ bounce rate rose 27 percent after it started its campaign against ad blockers, and page views fell close to 9 percent compared to views prior to the change. Average daily time on the site also declined by 9 percent.

The Washington Post is one of several publishers who gave blocking ad blockers a try only to back off after experiencing sharp declines in viewership, according to Anderson, who concludes that “instituting these deterrents is financially suicidal.” That sentiment is echoed by Doc Searls in a May 9, 2016, post on his blog on the Harvard University site. Searls quotes the report Interaction 2016 published by media investment firm GroupM:

Tracking and targeting intended to make advertising welcome makes it a nuisance. It is dysfunctional. The advertiser damages his reputation and pays to do so.

Even though sentiment is growing within the ad-tech community that things are going south fast – Searls quotes one ad-tech executive as referring to the industry as “a walking zombie” – other representatives of publishers and online ad networks continue their war against their own ad-blocking customers. One of their recent claims is that blocking ads breaches an implied contract between publisher and reader. In a September 25, 2015, article on Phys.org, David Glance dismantles this argument piece-by-piece.

To begin with, courts have long ruled that advertisements aren’t offers (with a small number of specific exceptions), they’re invitations to negotiate. (FindLaw offers a detailed discussion of the legal status of advertisements.) In a nutshell, a contract requires an offer, an acceptance, and bargained-for consideration. Glance points out that “visitors are never given the explicit choice to make that informed decision.”

Is visiting a site or using a free ad-supported app on your mobile phone tantamount to a contract of adhesion, which is similar to the boilerplate on the back of the ticket you take when you park your car in a commercial lot? Publishers may believe their terms of service create such a contract, but courts have ruled recently that the arbitration clauses included in such agreements are not legally binding, as Edward P. Boyle and Shahin O. Rothermel of Venable LLP explain in a May 6, 2016, post on Law360.

Also arguing against a contractual relationship between advertiser/publisher and site visitor is the fact that consumers aren’t told what exactly they are giving up in exchange for the personal data they surrender to the online ad trackers. In his Phys.org article, Glance points out that “in addition to the loss of privacy and the visual experience of ads, their data allocation is going to be used, web pages will load slower, and overall, their experience of the site will be diminished.”

For a contract to be valid, both parties must enter into it knowingly and voluntarily. How can you agree to a contract when the key terms are unknown? Consumers may know the value of what they’re getting, but they have no clue as to what exactly they are giving up in exchange, let alone having a reliable way to calculate its value.

The end of online advertising as we know it

In his Harvard blog post, Searls lists some of the many indications that the ad-tech bubble is popping. Ironically, the two companies that have profited the most from online ads – Facebook and Google – appear to be positioned to weather the transition to whatever form of online monetization comes next. Searls quotes an ad-tech executive who states that Facebook “owns the relationship with the user, and decides what content the user sees and how many see it.”

Google is reportedly working on an acceptable-ad policy similar to the one used by its nemesis, AdBlock Plus, according to Searls. At the same time, online-ad fraud seems to be on the decline. (I wrote about online-ad fraud most recently in the May 3, 2016, Weekly, as well as in the April 7, 2016, article, “More reasons why you need to block web ads.”)

Still, you should shed no tears for digital publishers or online ad networks. Nima Wedlake writes in an April 11, 2016, post on the Thomvest Ventures blog that in 2016 digital advertising will surpass TV ads for the top spot in total revenue, reaching $66 billion for the year. Mobile ad revenue is forecast to grow 30 percent annual through 2019, according to Thomvest research.

People will continue to block ads, and digital publishers will continue to make money in spite of it. It’s possible the online ad networks – and the companies that make their livelihood from them – will finally police themselves so the ads are less annoying and the tracking/data collection more transparent. (An opt-out function that boots the ads in exchange for micropayments would be a welcome addition.)

Whether the ad-tech industry can prevent itself from killing the goose that lays the golden eggs is a wide open question. For now, your best option remains to block ads while we wait for a safer and more palatable alternative.