Menu

Comcast battles Netflix, and everybody loses

When they put the squeeze on content providers, ISPs end up shortchanging their customers on the network speeds they promised them.

Is the Internet a public utility? Are Internet service providers common carriers? To date, the answer to both questions has been "no." The Internet's survival may depend on a 180-degree change in this perception. Netflix's recent agreement with Comcast highlights the dangers of a monopoly (Comcast) requiring that its customers pay twice for the same content.

(Image source: Apple Daily Report)

Wikipedia defines a public utility as "an organization that maintains the infrastructure for a public service (often also providing a service using that infrastructure)."

A common carrier is defined as "a person or company that transports goods or people for any person or company and that is responsible for any possible loss of the goods during transport."

Wikipedia further states that "[p]ublic utilities are subject to forms of public control and regulation ranging from local community-based groups to state-wide government monopolies." Likewise, "[a] common carrier offers its services to the general public under license or authority provided by a regulatory body."

So where does that leave the Internet? It is a valuable resource owned by no one, shared by nearly everyone, and managed by private entities, both nonprofit and for-profit. Ultimate control over the Internet's day-to-day operation is in the hands of a very small number of U.S. telecommunications companies.

Here's a primer on how the Internet works: Data travels between your browser and the people serving up the content you request via a handful of massive connection points. According to Backchannel's Susan Crawford in an October 30, 2014, article, 90 percent of the U.S.-based data on the Internet passes from sender to receiver through seven interconnection points located in New York City, Chicago, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Dallas, and Miami.

Comcast, Verizon, Time Warner Cable, CenturyLink, and AT&T own most of the ginormous transmission lines leading into the interconnection points. In fact, Comcast, Verizon, and Time Warner control half of the last-mile wired connections in the U.S., according to Crawford. They are their customers' sole source of Internet data, apart from the relatively small amount that travels over the cell network (which is also controlled by a handful of big-name services). The big ISPs are subject to very little government regulation, certainly much less regulation than public utilities and common carriers must comply with.

It has always been assumed that if traffic between any two of these interconnected networks exceeds their capacity, the networks would buy new capacity and the two entities would share the costs about equally. The hardware expenses aren't particularly great -- cable and servers are relatively cheap. (Crawford points out that most such upgrades are effected without requiring a formal contract.)

Not so long ago, something changed. Today a small number of big ISPs own the eyeballs, as Crawford puts it. And these eyeball networks -- such as Comcast and Time Warner, whose reach extends to the edge of the network -- want the people making the content that travels over their networks to pay some of the cost of managing the networks.

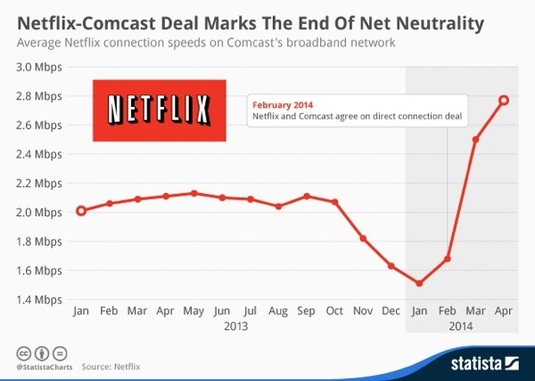

A very few eyeball networks exert a great amount of control over Netflix, Google, YouTube, and other content providers, whose livelihood depends on access to those eyeballs. If the eyeball networks choose to do nothing when their networks exceed their capacities, customers are shut out: the content takes forever to download, or it doesn't get delivered at all; the impact of the congestion is shown in the chart above.

Crawford tells the story of a small investment consultancy named NEPC whose telecommuters were unable to connect to the company's network. After much investigation, the company determined that the cause was a feud between Comcast and Netflix that affected NEPC's ISP, Cogent; Cogent had recently signed a big, nationwide transmission deal with Netflix.

Comcast and other eyeball networks allowed the Neflix-induced congestion on their networks to affect all their customers, not just the ones with Netflix accounts. For some customers, network speeds dropped to dial-up modem levels.

Why would a service provider allow its network's performance to degrade to such a point? Money. The ISPs -- Comcast in particular -- wanted Netflix and other content providers to pay for access to their captive eyeballs -- even if it meant their own customers wouldn't receive the broadband speeds they were paying for.

Netflix and others have labeled Comcast's ploy extortion, and it's difficult to see the situation any other way, considering that Netflix ultimately paid Comcast to deliver its content. As Crawford points out, customers are now paying twice for the same Internet access: once to Comcast and once to Netflix.

So Internet users aren't getting the high-speed bandwidth they are paying for, they're denied access to a video service they're paying for, and even customers who aren't using the video service are being cheated out of the bandwidth speeds they are paying for. There ought to be a law. There may soon be one -- maybe.

Federal Communications Commission Chairman Tom Wheeler is considering adoption of a hybrid classification for ISPs: They would be regulated as common carriers when dealing with content providers, but they'd be plain old unregulated information services when dealing with their "eyeball" customers -- the people who are consuming the content. In an October 30, 2014, article, Ars Technica's John Brodkin reports on the FCC's anticipated proposal.

The hybrid approach would allow ISPs to create fast lanes for select customers who are willing to pay extra for the higher data rates. It would also mean the end of pure net neutrality, but some people argue that the Internet hasn't been truly neutral in a long time -- if it ever really was.

Even with an in-between characterization for ISPs that subjects them to some government oversight, we'll still be paying twice for some content -- sort of like paying for the phone calls we receive as well as those we make.

Wait a minute -- we're doing that too!

Some people have suggested just the opposite of the FCC hybrid plan: treat ISPs as common carriers in their dealings with customers but as information services in their dealings with content providers. A primary reason the FCC opposes adding ISPs to the common-carrier category without qualification is that the agency doesn't want to have to justify contradicting its previous policy statements. Hey, things change, dudes. How about doing what's right for your constituency and worrying less about saving face?

The Internet is a public resource that needs to be regulated to ensure it serves the public and isn't monopolized by a handful of big corporations. Sounds like common-carrier territory to me.

Kupla kwik hits

Election-day blues: You already know a very small number of people have a very big impact on the outcome of elections. But you may not have realized just how few, how rich, and how white. In an October 31, 2014, article, The Nation's Zoe Carpenter reports that only 42 people (that's right, Larry, 42) are responsible for one-third of the spending by Super PACs in the 2014 election cycle.

Also not a surprise: All 42 of the superdonors are white, and all but seven are men. Carpenter cites data compiled by the Reflective Democracy Campaign that indicates white men account for 65 percent of elected officials, which is about twice their percentage of the total U.S. population. Rich white men tend to contribute to the campaigns of other white men. Duh!

So the influence of white men in politics increases as their percentage of the general population decreases. Add in the barriers being raised to potential minority voters and the trend away from public campaign financing (which in the past has served to even the contribution imbalance) and you get the rise of an elite minority class (rich white men) ruling over a disenfranchised majority (everybody else). What's democratic about that?

More than one way to amend the Constitution: Everybody hates Congress. Congress doesn't care what everybody thinks -- it's their ball, and if you don't want to play by their rules, you can go home.

Some Congress-haters at both ends of the political spectrum (and probably many points in between) are proposing to amend the Constitution by invoking the power granted to state legislatures via Article V of the Constitution. Nick Dranias and Lawrence Lessig make the case for such an approach in a November 2, 2014, article on Constitution Daily.

Such a convention convened by the states could only propose amendments -- the amendment process would otherwise be the same. Dranias and Lessig claim that the founding fathers intended Article V as a way for the states to rein in a runaway Congress. The Constitution is silent on how such a convention would operate, apart from it requiring two-thirds of the states to agree to calling one.

In the absence of guidelines, groups such as Dranias's Compact for America Educational Foundation are working to get states to agree to a format for an amendment-by-convention process. As Dranias and Lessig point out, our nation's founders provided us with tools for ensuring the perpetuation of our democracy. If the political insiders refuse to use these tools when necessary, it's up to the rest of us to step into the breach.

(As an aside, the state legislatures may not be any less corrupt than the U.S. Congress, at least according to John Oliver, who hosts HBO's Last Week Tonight. The Washington Post's Jaime Fuller reports on Oliver's most-recent rant in a November 3, 2014, article.)

Maybe half an Earth is all we need: Last year, the National Geographic Society awarded its highest prize, the Hubbard Medal, to Edward O. Wilson, an 84-year-old evolutionary biologist who believes that philosophy and religion are as important to human biology as genes and molecular structures.

In a November 2, 2014, interview on the National Geographic site, Wilson explains the connection between the humanities and human biology. But what really caught my eye was Wilson's proposal that humans abandon half the planet. The half-Earth concept is intended as an attempt to give all the other species on the planet a chance to thrive without having to deal with the destructive impact of us humans.

Humans have left their mark on nearly ever habitable inch of the Earth. One effect of our broad reach is that other species are dying off at extinction-event levels. So if humans can find a way to thrive while requiring a much smaller per-capita footprint, we could excuse ourselves from a goodly chunk of the orb and let nature do its magic without us getting in the way.

(Somewhere a boardroom full of oil-company executives is laughing so hard at this notion that they're soiling their Brionis.)

(Image source: Apple Daily Report)

Wikipedia defines a public utility as "an organization that maintains the infrastructure for a public service (often also providing a service using that infrastructure)."

A common carrier is defined as "a person or company that transports goods or people for any person or company and that is responsible for any possible loss of the goods during transport."

Wikipedia further states that "[p]ublic utilities are subject to forms of public control and regulation ranging from local community-based groups to state-wide government monopolies." Likewise, "[a] common carrier offers its services to the general public under license or authority provided by a regulatory body."

So where does that leave the Internet? It is a valuable resource owned by no one, shared by nearly everyone, and managed by private entities, both nonprofit and for-profit. Ultimate control over the Internet's day-to-day operation is in the hands of a very small number of U.S. telecommunications companies.

Here's a primer on how the Internet works: Data travels between your browser and the people serving up the content you request via a handful of massive connection points. According to Backchannel's Susan Crawford in an October 30, 2014, article, 90 percent of the U.S.-based data on the Internet passes from sender to receiver through seven interconnection points located in New York City, Chicago, Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Dallas, and Miami.

Comcast, Verizon, Time Warner Cable, CenturyLink, and AT&T own most of the ginormous transmission lines leading into the interconnection points. In fact, Comcast, Verizon, and Time Warner control half of the last-mile wired connections in the U.S., according to Crawford. They are their customers' sole source of Internet data, apart from the relatively small amount that travels over the cell network (which is also controlled by a handful of big-name services). The big ISPs are subject to very little government regulation, certainly much less regulation than public utilities and common carriers must comply with.

It has always been assumed that if traffic between any two of these interconnected networks exceeds their capacity, the networks would buy new capacity and the two entities would share the costs about equally. The hardware expenses aren't particularly great -- cable and servers are relatively cheap. (Crawford points out that most such upgrades are effected without requiring a formal contract.)

Not so long ago, something changed. Today a small number of big ISPs own the eyeballs, as Crawford puts it. And these eyeball networks -- such as Comcast and Time Warner, whose reach extends to the edge of the network -- want the people making the content that travels over their networks to pay some of the cost of managing the networks.

A very few eyeball networks exert a great amount of control over Netflix, Google, YouTube, and other content providers, whose livelihood depends on access to those eyeballs. If the eyeball networks choose to do nothing when their networks exceed their capacities, customers are shut out: the content takes forever to download, or it doesn't get delivered at all; the impact of the congestion is shown in the chart above.

Crawford tells the story of a small investment consultancy named NEPC whose telecommuters were unable to connect to the company's network. After much investigation, the company determined that the cause was a feud between Comcast and Netflix that affected NEPC's ISP, Cogent; Cogent had recently signed a big, nationwide transmission deal with Netflix.

Comcast and other eyeball networks allowed the Neflix-induced congestion on their networks to affect all their customers, not just the ones with Netflix accounts. For some customers, network speeds dropped to dial-up modem levels.

Why would a service provider allow its network's performance to degrade to such a point? Money. The ISPs -- Comcast in particular -- wanted Netflix and other content providers to pay for access to their captive eyeballs -- even if it meant their own customers wouldn't receive the broadband speeds they were paying for.

Netflix and others have labeled Comcast's ploy extortion, and it's difficult to see the situation any other way, considering that Netflix ultimately paid Comcast to deliver its content. As Crawford points out, customers are now paying twice for the same Internet access: once to Comcast and once to Netflix.

So Internet users aren't getting the high-speed bandwidth they are paying for, they're denied access to a video service they're paying for, and even customers who aren't using the video service are being cheated out of the bandwidth speeds they are paying for. There ought to be a law. There may soon be one -- maybe.

Federal Communications Commission Chairman Tom Wheeler is considering adoption of a hybrid classification for ISPs: They would be regulated as common carriers when dealing with content providers, but they'd be plain old unregulated information services when dealing with their "eyeball" customers -- the people who are consuming the content. In an October 30, 2014, article, Ars Technica's John Brodkin reports on the FCC's anticipated proposal.

The hybrid approach would allow ISPs to create fast lanes for select customers who are willing to pay extra for the higher data rates. It would also mean the end of pure net neutrality, but some people argue that the Internet hasn't been truly neutral in a long time -- if it ever really was.

Even with an in-between characterization for ISPs that subjects them to some government oversight, we'll still be paying twice for some content -- sort of like paying for the phone calls we receive as well as those we make.

Wait a minute -- we're doing that too!

Some people have suggested just the opposite of the FCC hybrid plan: treat ISPs as common carriers in their dealings with customers but as information services in their dealings with content providers. A primary reason the FCC opposes adding ISPs to the common-carrier category without qualification is that the agency doesn't want to have to justify contradicting its previous policy statements. Hey, things change, dudes. How about doing what's right for your constituency and worrying less about saving face?

The Internet is a public resource that needs to be regulated to ensure it serves the public and isn't monopolized by a handful of big corporations. Sounds like common-carrier territory to me.

Kupla kwik hits

Election-day blues: You already know a very small number of people have a very big impact on the outcome of elections. But you may not have realized just how few, how rich, and how white. In an October 31, 2014, article, The Nation's Zoe Carpenter reports that only 42 people (that's right, Larry, 42) are responsible for one-third of the spending by Super PACs in the 2014 election cycle.

Also not a surprise: All 42 of the superdonors are white, and all but seven are men. Carpenter cites data compiled by the Reflective Democracy Campaign that indicates white men account for 65 percent of elected officials, which is about twice their percentage of the total U.S. population. Rich white men tend to contribute to the campaigns of other white men. Duh!

So the influence of white men in politics increases as their percentage of the general population decreases. Add in the barriers being raised to potential minority voters and the trend away from public campaign financing (which in the past has served to even the contribution imbalance) and you get the rise of an elite minority class (rich white men) ruling over a disenfranchised majority (everybody else). What's democratic about that?

More than one way to amend the Constitution: Everybody hates Congress. Congress doesn't care what everybody thinks -- it's their ball, and if you don't want to play by their rules, you can go home.

Some Congress-haters at both ends of the political spectrum (and probably many points in between) are proposing to amend the Constitution by invoking the power granted to state legislatures via Article V of the Constitution. Nick Dranias and Lawrence Lessig make the case for such an approach in a November 2, 2014, article on Constitution Daily.

Such a convention convened by the states could only propose amendments -- the amendment process would otherwise be the same. Dranias and Lessig claim that the founding fathers intended Article V as a way for the states to rein in a runaway Congress. The Constitution is silent on how such a convention would operate, apart from it requiring two-thirds of the states to agree to calling one.

In the absence of guidelines, groups such as Dranias's Compact for America Educational Foundation are working to get states to agree to a format for an amendment-by-convention process. As Dranias and Lessig point out, our nation's founders provided us with tools for ensuring the perpetuation of our democracy. If the political insiders refuse to use these tools when necessary, it's up to the rest of us to step into the breach.

(As an aside, the state legislatures may not be any less corrupt than the U.S. Congress, at least according to John Oliver, who hosts HBO's Last Week Tonight. The Washington Post's Jaime Fuller reports on Oliver's most-recent rant in a November 3, 2014, article.)

Maybe half an Earth is all we need: Last year, the National Geographic Society awarded its highest prize, the Hubbard Medal, to Edward O. Wilson, an 84-year-old evolutionary biologist who believes that philosophy and religion are as important to human biology as genes and molecular structures.

In a November 2, 2014, interview on the National Geographic site, Wilson explains the connection between the humanities and human biology. But what really caught my eye was Wilson's proposal that humans abandon half the planet. The half-Earth concept is intended as an attempt to give all the other species on the planet a chance to thrive without having to deal with the destructive impact of us humans.

Humans have left their mark on nearly ever habitable inch of the Earth. One effect of our broad reach is that other species are dying off at extinction-event levels. So if humans can find a way to thrive while requiring a much smaller per-capita footprint, we could excuse ourselves from a goodly chunk of the orb and let nature do its magic without us getting in the way.

(Somewhere a boardroom full of oil-company executives is laughing so hard at this notion that they're soiling their Brionis.)