Menu

|

Why is it that the people who know the most about how the Internet works are the least likely to share their personal information on the Internet?

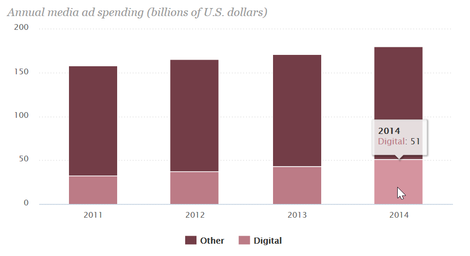

The short answer: The more you share, the easier it is for you to be taken advantage of. Facebook is in trouble with France’s data protection authority, CNIL (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés), because the company tracks non-users, which violates the French Data Protection Act. Forbes’ Abigail Tracy reports in a February 9, 2016, article that one of Facebook’s illegal practices was tracking people who do not have Facebook accounts. Whenever a person visits a public Facebook site, they receive a tracking cookie from the company. Nearly every commercial site we visit deposits a tracker in our cookie folder as soon as it opens in our browsers. The CNIL objects to Facebook receiving “information relating to third-party websites offering Facebook plug-ins (e.g. Like button) that are visited by Internet users,” as TechCrunch’s Natasha Lomas writes in another February 9, 2016, article. CNIL also found that Facebook fails to inform people about its commercial use of their tracking information, and the company also neglects to get visitors’ consent to be tracked. Another area in which Facebook comes up short, according to the French agency, is its failure to allow users to prevent data collection for advertising purposes. This practice alone constitutes a breach of the right to privacy, in the data-protection authority’s estimation. Facebook says it is reviewing the French agency’s report. A spokesperson responded that the company is “confident that we comply with European Data Protection law” and looks forward to “engaging” CNIL about its concerns. (Facebook was also accused by the CNIL of continuing to use the Safe Harbor mechanisms that recently expired; the negotiations to replace those provisions were the topic of last week’s Weekly. The new agreement, reached two days after Safe Harbor expired, has been roundly criticized for a provision that calls for the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence to send “annual written assurances” that data transferred from Europe to the U.S. will not be subject to indiscriminate mass surveillance. In a February 2, 2016, article, CommonDreams’ Lauren McCauley covers criticism by Edward Snowden and other privacy advocates, who claim that the agreement lacks any legally binding element.) How the trackers convert cookies into cash Few of us know or care what companies do with the personal information they collect about us. That’s too bad. Back in 2009 the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Peter Eckersley explained the basics of third-party tracking on the web. When you visit a site, your browser discloses information about you and your hardware and software setup, including a unique identifier. The cookies that advertisers rely on combine the browser information with your browsing history to create your profile. The site presents your profile to ad networks, which match profiles to the ads of their clients based on the clients’ criteria: a simple example is people whose profile indicates they’re likely to purchase shoes being served ads for Zappos. Things get more complicated when your profile doesn’t match any of the ad network’s inventory. Your profile is put up for auction – in just milliseconds. It is matched with other information the ad network knows about you, and a bid is generated. The winning bidder gets to serve you an ad from its stockpile based on the information in your ever-growing profile. (Gizmodo’s Adam Clark Estes explains the ad-auction process in a February 25, 2014, article.) All those online ads translated into revenues of $50.7 billion in 2014, according to the Pew Research Center’s State of the News Media 2015. That’s an 18 percent increase from the $43.1 billion in revenues in 2013. Digital ads accounted for 28 percent of total ad revenue in 2014, up from 25 percent of total ad revenue in 2013. Spending on video web/mobile ads increased 56 percent in 2014 from the year earlier and now represents 27 percent of all display-ad spending, according to the report. The bulk of digital-ad revenue goes to five companies: Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Yahoo, and AOL accounted for 61 percent of total online ad revenue in 2014, although their collective share has declined 1 percentage point each year since 2010. Google’s share actually declined to 38 percent of the total in 2014, or $19.7 billion, from 40 percent, or $17.1 billion, in 2013. Facebook recorded $5 billion in digital ad revenue in 2014 (10 percent of the total), which is up 52 percent from $2.2 billion in ad revenue in 2012. What you search for can hurt you: Online-ad profiling’s socio-economic implications If you search Google for terms such as “can’t pay rent” or “need fast cash,” you could be targeted in the results with ads for payday loan services, even though such ads violate Google’s own prohibition against “predatory financial advertising,” as the Atlantic’s Adrienne LaFrance writes in a November 3, 2015, article. The ads are placed by lead generators that compile consumer profiles and then sell them to all comers. This is how payday-loan operators and other predatory “services” are able to skirt the law and Google’s own policies. At a U.S. Federal Trade Commission workshop in late 2015, one consumer advocate stated that the online-ad ecosystem represents a “consumer protection problem of both deception, and unfairness, and maybe abuse as well.” As LaFrance writes, “[c]ompanies and individuals are working together to target consumers on a personal level, to use their most vulnerable Google searches against them.” Maybe some of the companies we transact with have our best interests at heart, but not all of them do. In a February 8, 2016, article on Forbes, Steve Denning explains why so many Wall Street firms are concerned about publicly funded companies being driven solely by short-term stock market performance. The blame is placed on “dissident shareholders” and “activist hedge funds and managements.” A few corporate ideologues may stomp and storm about the need for a long view when guiding public companies into an increasingly uncertain future, but the focus on short-term profitability isn’t going to change anytime soon – if ever. That goes double for Internet companies that make their money by selling what they know about their “customers.” In fact, their users are really their raw material. The companies fashion the private data their users readily serve up for free into valuable market intelligence. Remember, if you didn’t pay for it, you’re the product. The current online exchange rate – use of a service in trade for unfettered and unlimited access to your thoughts, activities, and social and professional contacts – is a bad deal for consumers. We’re getting taken, left, right, and center. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Short list Cool links I don't have time to write about: Online Journalism Blog: Create a tweet archive for your feed or someone else’s The Atlantic: Data from license-plate readers for sale, privacy imperiled Electronic Frontier Foundation: Automated license-plate readers FAQ AlterNet: Google skews search results to combat extremists Electronic Frontier Foundation: Copyright abuse - college student prosecuted for sharing another student's master's thesis Medium/MIT Media Lab: More copyright abuse - the demise of movie rentals allows owners to restrict access Forbes: ChangeTip Contribute debuts as a micropayment alternative to deceptive, dangerous online ads AdNews: The growing threat of malvertising - and how to protect yourself |