Menu

How to combat hate and harassment on the Internet

Free speech does not mean you can say anything to anyone, anytime, anywhere. Time, place, and manner restrictions prohibit "fighting words" that are intended to incite imminent violence or other crime. They also make it illegal to shout "fire" in a crowded theater or to make other statements that could endanger people or property. In addition, you can't defame someone by damaging them with statements that you know, should know, or have reason to believe are false.

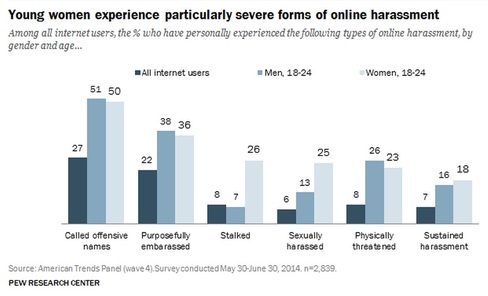

Things get murky when it comes to free-speech limits on the Internet. A survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in June 2014 and published in October 2014 found that 40 percent of Internet users have been harassed online, and 73 percent have witnessed someone else being harassed on the Internet. The harassment they witnessed includes being called offensive names (60 percent), being embarrassed on purpose (52 percent), physical threats (25 percent), sexual harassment (19 percent), and stalking (18 percent).

Things get murky when it comes to free-speech limits on the Internet. A survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in June 2014 and published in October 2014 found that 40 percent of Internet users have been harassed online, and 73 percent have witnessed someone else being harassed on the Internet. The harassment they witnessed includes being called offensive names (60 percent), being embarrassed on purpose (52 percent), physical threats (25 percent), sexual harassment (19 percent), and stalking (18 percent).

Young women are most likely to be the target of what the researchers refer to as "severe" harassment: physical threats, sustained harassment, sexual harassment, and stalking.

Most of the harassment occurs on social media: 66 percent of the Internet users who report being harassed said it happened while they were using a social networking site or app. The next two most-common sources of harassment identified by the survey respondents are the comments sections of web sites (22 percent) and online gaming sites (16 percent). While 27 percent of the harassment victims report being extremely or very upset by the actions, only 5 percent reported the harassment to law enforcement.

The most-effective response to harassment: Power in numbers

As Nadia Kayyali and Danny O'Brien of the Electronic Frontier Foundation explain in a January 8, 2015, essay, the Internet doesn't cause the harassment, it merely reflects the offline world. However, communications of all types are easier on the Internet -- often for the better, but sometimes for the worse.

In addition to threats of physical harm, offline stalking, sexual harassment, and actual assaults, Kayyali and O'Brien define the threshold of criminal harassment as encompassing any action that causes "extreme levels of targeted hostility, often accompanied by the exposure of their private lives." The harassment is frequently intended to stifle the victim's right to speak freely, particularly when the attacks are coordinated by members of a group.

One of the most effective responses to this type of harassment is what the EFF refers to as "counter-speech," which attacks the harassers using the same techniques they used to perpetrate the harassment. Kayyali and O'Brien point out that laws intended to combat online (and offline) harassment are rarely enforced, or they're enforced "unfairly and ineffectively." Also, such laws threaten to inhibit protected speech.

Depending on the service providers to combat online harassment won't work because businesses are most interested in maximizing profitability and limiting their own liability. They are thus likely to act in ways that may stifle protected speech and/or fail to keep their customers safe in an effort to protect their bottom line.

The EFF recommends a two-pronged approach to combating online harassment: first, enforce existing defamation laws and time-place-manner restrictions; and second, empower users by making it easier for them to filter harassing messages and limit the dissemination of their personal information.

Admittedly, the two prongs are somewhat contradictory. The first requires that victims report instances of hate and harassment. The goal is to overwhelm the haters with counter-speech in the form of official warnings and the real potential of legal actions. The second prong is the standard approach of ignoring the "trolls" in hopes that the silence will discourage them. As many victims of harassment will attest, this doesn't always work.

In a June 16, 2014, column in the New York Times, Jake Flanagin provides several examples of persistent harassment. In one case, a woman has been stalked on Twitter for more than four years. As much as victims want to believe online threats are empty, the safest response is to document the harassment and notify the services the harassers use, as well as the appropriate authorities -- despite the fact that there may not be much either can do to prevent the abuse.

If you believe you or someone you know has been the victim of criminal harassment, report it to whichever service the harassers are using via the service's "report abuse" option. In an August 8, 2013, CNET post I described how to report problems to Google, Facebook, and other web services. You can also file a complaint with the Internet Crime Complaint Center. The U.S. Department of Justice provides information on reporting computer, Internet-related, and intellectual property crime. If the harasser is close to home, contact your local police.

Most of the harassment occurs on social media: 66 percent of the Internet users who report being harassed said it happened while they were using a social networking site or app. The next two most-common sources of harassment identified by the survey respondents are the comments sections of web sites (22 percent) and online gaming sites (16 percent). While 27 percent of the harassment victims report being extremely or very upset by the actions, only 5 percent reported the harassment to law enforcement.

The most-effective response to harassment: Power in numbers

As Nadia Kayyali and Danny O'Brien of the Electronic Frontier Foundation explain in a January 8, 2015, essay, the Internet doesn't cause the harassment, it merely reflects the offline world. However, communications of all types are easier on the Internet -- often for the better, but sometimes for the worse.

In addition to threats of physical harm, offline stalking, sexual harassment, and actual assaults, Kayyali and O'Brien define the threshold of criminal harassment as encompassing any action that causes "extreme levels of targeted hostility, often accompanied by the exposure of their private lives." The harassment is frequently intended to stifle the victim's right to speak freely, particularly when the attacks are coordinated by members of a group.

One of the most effective responses to this type of harassment is what the EFF refers to as "counter-speech," which attacks the harassers using the same techniques they used to perpetrate the harassment. Kayyali and O'Brien point out that laws intended to combat online (and offline) harassment are rarely enforced, or they're enforced "unfairly and ineffectively." Also, such laws threaten to inhibit protected speech.

Depending on the service providers to combat online harassment won't work because businesses are most interested in maximizing profitability and limiting their own liability. They are thus likely to act in ways that may stifle protected speech and/or fail to keep their customers safe in an effort to protect their bottom line.

The EFF recommends a two-pronged approach to combating online harassment: first, enforce existing defamation laws and time-place-manner restrictions; and second, empower users by making it easier for them to filter harassing messages and limit the dissemination of their personal information.

Admittedly, the two prongs are somewhat contradictory. The first requires that victims report instances of hate and harassment. The goal is to overwhelm the haters with counter-speech in the form of official warnings and the real potential of legal actions. The second prong is the standard approach of ignoring the "trolls" in hopes that the silence will discourage them. As many victims of harassment will attest, this doesn't always work.

In a June 16, 2014, column in the New York Times, Jake Flanagin provides several examples of persistent harassment. In one case, a woman has been stalked on Twitter for more than four years. As much as victims want to believe online threats are empty, the safest response is to document the harassment and notify the services the harassers use, as well as the appropriate authorities -- despite the fact that there may not be much either can do to prevent the abuse.

If you believe you or someone you know has been the victim of criminal harassment, report it to whichever service the harassers are using via the service's "report abuse" option. In an August 8, 2013, CNET post I described how to report problems to Google, Facebook, and other web services. You can also file a complaint with the Internet Crime Complaint Center. The U.S. Department of Justice provides information on reporting computer, Internet-related, and intellectual property crime. If the harasser is close to home, contact your local police.

FCC chairman proposes redefining 'broadband' as at least 25Mbps downstream, 3Mbps upstream

Each year, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission issues the Annual Broadband Progress Report, as mandated by Congress. In the draft of the most recent report, FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler proposes changing the definition of "broadband" from the current 4Mbps downstream and 1Mbps upstream to 25Mbps downstream and 3Mbps upstream.

Ars Technica's Jon Brodkin reports in a January 7, 2015, article that Wheeler believes the higher speeds are required to meet the mandate in the Telecommunications Act of 1996 for "advanced telecommunications capabilities" sufficient to "enable users to originate and receive high-quality voice, data, graphics, and video telecommunications using any technology."

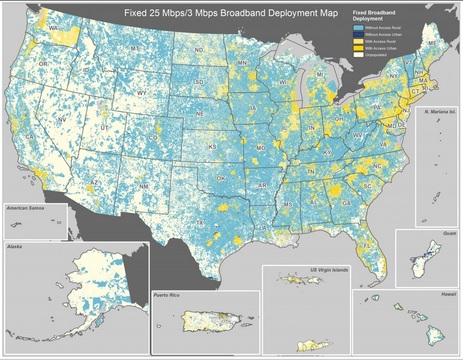

ISPs would not be required to satisfy the 25/3 standard for government-funded projects, but an FCC official indicated that several dozen "rural broadband experiments" being funded by the agency would offer speeds at that level or greater. The FCC believes ISPs are not moving fast enough to expand their broadband offerings. Data released by the agency indicate that while 92 percent of people in urban areas of the country have access to 25/3 Internet service, only 47 percent of people in rural areas have access available at those speeds. The map above shows the distribution (click to enlarge).

In a related move, Wheeler is ready to reclassify ISPs as "common carriers" subject to government regulation under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934. Ars Technica's Megan Geuss explains in another January 7, 2015, article that Title II will be the basis for the FCC's net neutrality rules for the broadband industry. ISPs complain that such regulation would stifle innovation, but Wheeler is confident the Title II rules can be applied in a way that will not deter investment in new Internet infrastructure and services.

Each year, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission issues the Annual Broadband Progress Report, as mandated by Congress. In the draft of the most recent report, FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler proposes changing the definition of "broadband" from the current 4Mbps downstream and 1Mbps upstream to 25Mbps downstream and 3Mbps upstream.

Ars Technica's Jon Brodkin reports in a January 7, 2015, article that Wheeler believes the higher speeds are required to meet the mandate in the Telecommunications Act of 1996 for "advanced telecommunications capabilities" sufficient to "enable users to originate and receive high-quality voice, data, graphics, and video telecommunications using any technology."

ISPs would not be required to satisfy the 25/3 standard for government-funded projects, but an FCC official indicated that several dozen "rural broadband experiments" being funded by the agency would offer speeds at that level or greater. The FCC believes ISPs are not moving fast enough to expand their broadband offerings. Data released by the agency indicate that while 92 percent of people in urban areas of the country have access to 25/3 Internet service, only 47 percent of people in rural areas have access available at those speeds. The map above shows the distribution (click to enlarge).

In a related move, Wheeler is ready to reclassify ISPs as "common carriers" subject to government regulation under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934. Ars Technica's Megan Geuss explains in another January 7, 2015, article that Title II will be the basis for the FCC's net neutrality rules for the broadband industry. ISPs complain that such regulation would stifle innovation, but Wheeler is confident the Title II rules can be applied in a way that will not deter investment in new Internet infrastructure and services.

A tribute to journalists killed in the line of duty

At least 60 journalists were killed in the course of doing their job worldwide in 2014, according to a report by the Committee to Protect Journalists. That number is actually fewer than the 70 journalist deaths recorded by the group in 2013, and the 74 deaths confirmed in 2012 and 2009.

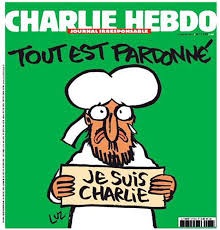

The first two weeks of 2015 show that threats to journalists continue. On the day after the murder of 12 staff members of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, Nerlita "Nerlie" Ledesma, a reporter for a newspaper in the Bataan province of the Luzon in the Philippines, was gunned down. According to a January 8, 2015, article by Human Rights Watch's Phelim Kine, Ledesma's death is under investigation and has not yet been confirmed as the result of her work for the newspaper she worked for in the city of Balanga.

The Philippines has been a particularly dangerous place for journalists to ply their trade. The murderers of at least 34 journalists on November 23, 2009, in what is called the Maguindanao massacre, have yet to face justice. The Wikipedia entry describing the massacre indicates that as of August 2014, no one has been convicted of the murders, although trials of several dozen suspects are ongoing.

According to Wikipedia, the last journalist killed in the line of duty in the U.S. was Chauncey Bailey of the Oakland Post on August 2, 2007. Just last month, American photojournalist Luke Somers was killed during a failed rescue attempt in Yemen, as USA Today's Kim Hjelmgaard reported in a December 6, 2014, article.

To the family, friends, and colleagues of all journalists killed in action -- and all victims of hatemongers and their misguided minions -- my heartfelt condolences. May they rest in peace.

At least 60 journalists were killed in the course of doing their job worldwide in 2014, according to a report by the Committee to Protect Journalists. That number is actually fewer than the 70 journalist deaths recorded by the group in 2013, and the 74 deaths confirmed in 2012 and 2009.

The first two weeks of 2015 show that threats to journalists continue. On the day after the murder of 12 staff members of the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, Nerlita "Nerlie" Ledesma, a reporter for a newspaper in the Bataan province of the Luzon in the Philippines, was gunned down. According to a January 8, 2015, article by Human Rights Watch's Phelim Kine, Ledesma's death is under investigation and has not yet been confirmed as the result of her work for the newspaper she worked for in the city of Balanga.

The Philippines has been a particularly dangerous place for journalists to ply their trade. The murderers of at least 34 journalists on November 23, 2009, in what is called the Maguindanao massacre, have yet to face justice. The Wikipedia entry describing the massacre indicates that as of August 2014, no one has been convicted of the murders, although trials of several dozen suspects are ongoing.

According to Wikipedia, the last journalist killed in the line of duty in the U.S. was Chauncey Bailey of the Oakland Post on August 2, 2007. Just last month, American photojournalist Luke Somers was killed during a failed rescue attempt in Yemen, as USA Today's Kim Hjelmgaard reported in a December 6, 2014, article.

To the family, friends, and colleagues of all journalists killed in action -- and all victims of hatemongers and their misguided minions -- my heartfelt condolences. May they rest in peace.