Menu

|

The new browser wars: Thou shalt not block our ads and trackers

Web publishers claim the new Brave ad-blocking browser infringes their copyrights and trademarks, but what is it exactly the publishers are claiming as their copyrights and trademarks? Ads? Tracking? Or are they attempting to enforce a legal right to monetize the data they collect about their site visitors?

|

On April 7, 2016, a group of major-league publishers – including the New York Times, the Washington Post, McClatchy, Gannett, and Dow Jones – sent a letter to Brendan Eich (pdf), the founder and CEO of Brave Software, warning of legal action if the Brave browser replaces the ads that accompany their content with ads of Brave’s choosing.

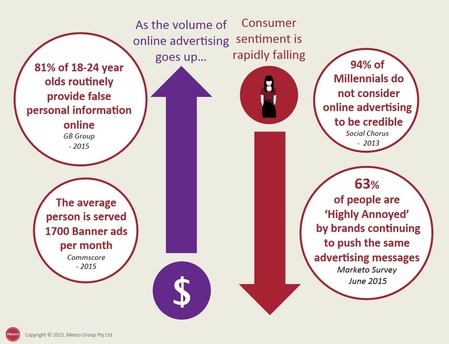

The publishers claim the Brave browser’s presentation of their public web content violates their trademarks and copyrights (also “other laws,” but let’s stick with trademark and copyright for now). Brave doesn’t alter the site content or trademarks. It replaces the ads that accompany the content and trademarks with ads of its own that don’t track you – or don’t track you quite so closely. Are the publishers claiming the ads and the tracking that goes with them are subject to the publishers’ legally protected trademarks and copyrights? What is it precisely that the publishers are claiming copyrights and trademarks to? They don’t even know what specific ads a person is going to be shown along with the content. Are web publishers actually claiming a right to track and monitor their readers/viewers/customers? And are they also asserting a right to resell and otherwise monetize the information they collect as a result of their tracking and monitoring? What laws apply to protect the value of the data collected by web trackers? Tortious interference with contracts, business relationships, or perspective business opportunity, perhaps? The publishers’ letter to Eich doesn’t cite any particular statute other than the federal copyright law, 17 U.S.C. § 504. However, it states that the Brave browser “deceiv[es] consumers and unlawfully appropriate[es] our work.” Browsers always render web-page content differently. Ad blocking browser extensions are far from the only programs that change the way a page opens in your browser. Are the publishers claiming that certain browser features or extensions unlawfully represent the content of their websites? Several browser add-ons let you view a web page as text-only. Are they also violating the site’s copyrights and trademarks? Are they deceiving consumers and unlawfully appropriating their work? The actual text content of the site is unchanged. What legal justification are the publishers citing to extend their trademarks and copyrights to ads and other non-essential (for users) elements of the pages on which the content is presented? The big leap from information presenter to information provider The publishers’ letter to Eich and Brave Software states that the browser’s reworking of the publishers’ pages is tantamount to “a plan to steal our content to publish on your own website.” In other words, Brave isn’t a browser at all. It’s a virtual website. As with the legal justification of extending trademarks and copyrights to intangible, unpredictable elements (ads and tracking), what case law, regulations, or statutes lay the groundwork for determining that a browser has been transformed from a facilitator to a competitor? It's no surprise that web publishers would see Brave’s proposed business model as a threat to their livelihood. A study released recently by Australian security firm Meeco Group (pdf) found that publishers are the only ones who benefit from online ads. Not advertisers, not consumers – just the publishers in the middle. The study is based on click-through rates, cost per click, and other data from 2012, but Meeco claims online ad costs have increased in the interim, so their figures understate actual costs to online advertisers today. It cost advertisers an average of $13.61 for each ad that was “converted” into a lead, not a sale. Of the 12.78 billion ads that were served in one three-month period, only 0.018 percent were converted. As Meeco puts it, 12.5 billion of the ads were shown to “an uninterested audience.” Use of ad blockers increased by 41 percent in 2015, according to figures released by Adobe and ad-blocking nemesis Pagefair; ad blocking is projected to cost advertisers and distributors $41 billion in 2016. Consumers find the ads irritating, and they don’t like being tracked, according to Meeco, while advertisers are spending more money to attract fewer potential customers, and they’re losing the trust of consumers. Online ads are a boon to publishers, a bane to brands and consumers So who’s happy about the current online-ad system? Publishers, who are serving up more and more ads, collecting more and more revenue from the ads, and otherwise benefiting from the increased competition for consumers’ attention. Meeco proposes replacing the current online-ad system with one in which customers deal directly with brands. Consumers would spend their “personal data assets” as a new form of currency in transactions based on stated intentions rather than on advertising profiles. The key is that personal data is exchanged knowingly and voluntarily, with “permissions on the user’s terms.” (It just so happens that Meeco is offering one such system that claims to connect brands to consumers directly, with no publisher/advertiser middleman.) When it comes to personal data collection, consumers are in the dark. That’s precisely where online ad networks and web publishers want to keep them. Brands just want to reach customers who want or need their products, and to do so as efficiently and inexpensively as possible. A system that removes the intermediaries and puts more power into consumers’ hands is worth taking out for a test drive. Having more control over the collection and use of your personal information is the cherry on top. |