Menu

|

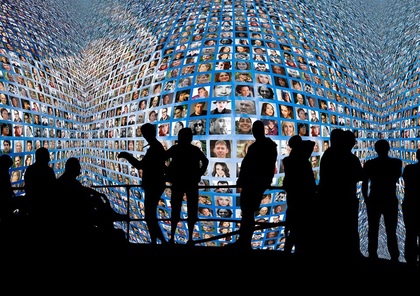

How we lose ourselves in private data collection

|

The companies, government agencies, and other organizations we interact with compile some of what they learn about us into products that they sell or otherwise profit from. They own the information they have collected and analyzed even though it pertains to us. What they do with the information, and whether or not they protect it from being stolen and used against us criminally, is entirely out of our control.

Many people are okay with this. It’s just part of the price of living in the modern world. As surveillance expands and data from more sources are integrated, we lose “ownership” of what makes us us. Last week’s Weekly explained how the digital economy is driven by personal data collection – an ever-increasing amount of private-information gathering, analysis, resale, and reuse. Thomas Hemnes explains in a December 1, 2012, post on the Privacy Advisor blog that compilations of personal data are the property of the organization that does the compiling. The prototypical example is a company’s customer list, which is comprised of names and other information about the people and organizations the business transacts with. The lists are trade secrets and are thus protected from unauthorized use. They’re also protected by the U.S. Copyright Act and similar laws in the U.K., European Union, and other international jurisdictions. As Hemnes writes, “[t]he compilations of facts that comprise my digital identities are subject to ownership, but the owner is not me; it’s the compiler.” From a legal perspective, the private-data compilations are considered “dangerous instrumentalities” that “must be regulated to avoid harm or unlawful exploitation.” The collection of private information about consumers is encouraged by public agencies and private companies. It is good for business. According to Hemnes, the collection of the data is unregulated, but use of the data is “regulated and controlled.” How is data use “regulated and controlled”? When you consider the growing number of data breaches entailing personally identifiable information (PII), you realize there is insufficient enforcement of regulations governing how the information is stored and used. (Michael McFarland’s Privacy and the Law provided by Santa Clara University’s Markula Center for Applied Ethics offers a soup-to-nuts look at the state of privacy law.) Further, the compilers face no real penalty for losing or misusing the PII they collect and maintain. Courts have consistently rejected all claims by consumers of damages resulting from the theft of their private information, ruling the consumers suffered no compensable monetary loss. Extending intellectual-property protection to consumers’ private information Hemnes concludes that your identity cannot be considered a personal possession: It belongs to everyone as part of the commons. Not everyone agrees In her paper “Personal Information as Intellectual Property” (pdf), Santa Clara University School of Law Professor Dorothy J. Glancy posits that U.S. law already has many examples of intellectual property-like protections applied to personal information, although the information has not yet been classified as intellectual property. Glancy states that once personal information is shared, it is transformed from the intellectual property of the person it relates to, into the shared property of that person and everyone who collects and reuses it. Intellectual property protections can still be applied to the resulting co-owned data in a way that provides the person who is the source of the information with a measure of control over how the data is stored and used. It also avoids charges of unjust enrichment by the information collectors, who profit at the expense of the person to whom the data relates. Arguments against treating personal information as intellectual property claim it is inhuman to treat people as commodities – even though it happens all day, every day. They add that limiting the collectors’ ability to take note of what is readily observable, and thus public, is an unconstitutional restriction on the collectors’ freedom of expression. The protections would also prevent information about public figures from being made public, particularly “politically and economically powerful people,” according to Glancy. The critics state that there are better ways to protect the information than to create a new class of intellectual property. Extending trade-secrets principles to personal information In “Privacy as Intellectual Property?” (pdf), Pamela Samuelson, UC Berkeley Professor of Information Management and of Law, argues that trade secrecy provides better protection for personal information, without requiring that the law create a new property right. Samuelson describes three areas where trade secrets and private information protection coincide:

Samuelson points out that trade-secret law is currently split in two camps: the “property school” and the “confidential relationship school.” She deems the latter more appropriate in terms of both trade secrets and personal information because the right depends on the owner’s ability to control the behavior of the other parties in the relationship, as opposed to a right that is “good against the world” in and of itself, as a typical property right would be. Personal information is a valuable commodity, but it’s still personal. Even so-called anonymized information poses a threat to our well-being if it is misused. The amount of personal information collected is going nowhere but up. It might be a good idea to establish legal standards for protecting us from abuse or negligence by the data collectors. |