Menu

Five indications that we are currently between regimes |

Change. You gotta love it, even if it seems sometimes to do more harm than good -- at least at first.

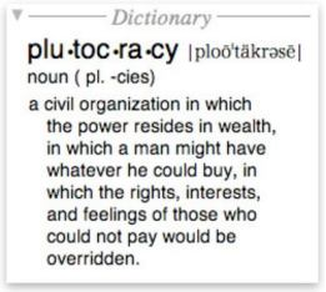

Lately I've been reading a lot about situations that are stuck between the old and the new. The traditional rules are still being applied to entirely new problems, and the result is a mess. Yet there's hope that with time, the rules will catch up with the new realities, and we'll all live happily ever after. Well, happier ever after, maybe. Here are five examples of outdated rules, policies, and practices being misapplied in the burgeoning Internet age. 1) Welcome to the Interregnum Interregnum: A period when normal government is suspended, especially between successive reigns or regimes; an interval or pause. An alternative definition of "interregnum" is offered by progressive journalist Chris Hedges in a June 5, 2015, interview with Salon's Elias Isquith that was published on the AlterNet site: "[The] period where the ideas that buttress the old ruling elite no longer hold sway, but we haven’t articulated something to take [their] place." Hedges also compares the current widespread disenchantment with the U.S. political system to a "a pot that's just beginning to boil." The facade of the status quo remains intact even while tremendous change is occurring invisibly, below the surface. Hedges quotes John Ralston Shaw, who said the U.S. has "undergone a corporate coup d'état in slow motion." It's like people are gradually waking up to their loss of political power. Fewer and fewer people bother to vote because they know doing so is pointless. As Hedges says, "If we think that voting for Hillary Clinton … is really going to make a difference, then I would argue we don’t understand corporate power and how it works." If it doesn't matter who you vote for, maybe the problem is the wrong people are running for office. We need candidates who are truly independent, who belong to no political party, and who have no other affiliation, for that matter. We need candidates who won't take any campaign contributions, simply because they have no intention of "campaigning." That's why I propose we all run for office. Everybody for President! (Or Senator, or Congressman, or Dog Catcher, for that matter.) Then we all vote for ourselves and have one monster of a runoff election. Okay, so maybe that wouldn't be the best solution, but we do need candidates who will listen only to their constituents rather than to lobbyists and other politicians. In a truly open government, our representatives would serve only as conduits for the will of the people they represent. The politicians wouldn't be the ones deciding for themselves what legislation they want to propose and how they vote on pending bills. Instead, they would act as the consensus of their constituents dictate. Can the Internet convert our current indirect democracy to a more direct one? Could our representatives serves as moderators, mediators, even conciliators of the policies that the electorate itself proposes and disposes? Nah, I know it's a pipe dream. But imagine how disruptive the Internet could be to politics and the electoral process if we truly had an open government, where nothing happens behind closed doors, where all the business of the people is made available to all the people in a way that allows them to influence and otherwise act upon it directly. The first step is to conceive it. The next step is to get enough people to believe it's worth giving a try. Considering the sad state of the current U.S. political process, what have we got (left) to lose? 2) Busting the myth about consumer willingness to trade privacy for free services Facebook, Google, and other monster web services claim that their users are happy to trade their privacy in exchange for free use of the companies' services. A study (pdf) conducted by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of New Hampshire found that most people in the U.S. believe the "data for discounts" model is a raw deal for consumers. Instead, people are resigned to losing their privacy in exchange for use of web services, even though more than half of the people surveyed expressed a desire to maintain control over their personal information. They believe the privacy train has already left the station. The researchers also report finding "broad public fear about what companies can do with the data," as TechCrunch's Natasha Lomas writes in a June 6, 2015, article. So, much like the disenchantment of U.S. citizens with their government, people are unhappy with -- even afraid of -- the companies they deal with on the web, but they don't yet know what to do about it. 3) Apple's Tim Cook calls out Google and Facebook on privacy violations When the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) honored Apple CEO Tim Cook at its annual Champions of Freedom event, it marked the first time the honor was given to a business person. Past EPIC honorees include privacy advocate and security researcher Bruce Schneier, and Stanford Law lecturer Chip Pitts. In his address at the event in Washington, DC, on June 1, 2015, Cook took aim at Facebook, Google, and other tech companies that profit by selling the personal information they collect about their "customers." As TechCrunch's Matthew Panzarino reports in a June 2, 2015, article, Cook said "some of the most prominent and successful companies [in Silicon Valley] have built their businesses by lulling their customers into complacency about their personal information." Cook hints that a reckoning is due for these services once consumers wake up to the bad deal they're getting: "You might like these so-called free services, but we don’t think they’re worth having your email, your search history and now even your family photos data mined and sold off for god knows what advertising purpose. And we think some day, customers will see this for what it is.” I've got two words for it: Unjust enrichment. 4) Ad blocking may force a new Internet revenue model Another sad fact that Internet denizens are slowly realizing is that web ads are more than a nuisance -- they're dangerous. Not only do the ad networks spy on us, they sometimes are infiltrated by malware purveyors who craft ads that infect the machines on which the ads appear. TechCrunch's Danny Crichton writes in a June 7, 2015, article that the number of people using ad-blocking software increased from 40 million in 2012 to 200 million today. Advertisers have only themselves to blame. They have increased the number of trackers in their ads so much that a typical site is likely to plant dozens of separate trackers on your machine. Not only do these trackers make the pages dog-slow to load, they are aggregating their data collecting to create incredibly detailed dossiers on web users. Crichton calculates that if everyone paid $14.17 a month, the entire online ad universe could be dumped once and for all. That's 10 percent to 20 percent more than what most of us are already paying for Internet access. (Crichton claims this estimated amount is actually too high because it doesn't factor in the costs to the services associated with designing and delivering the ads themselves.) None of the proposals for replacing the current spying ad networks is without its pitfalls: Getting so-called content providers to join forces in offering subscriptions for content has proven nearly impossible, and web users are averse to voluntary micropayments -- a fact to which I can attest personally. What's most likely to happen is creation of an entirely new revenue model -- somehow, somewhere. Once again, we appear to be in an "interregnum" period -- the old rules no longer work, but the new rules haven't yet been devised, let alone implemented. 5) Pay for a private version of Facebook? One potential new web-revenue paradigm is suggested by Zeynep Tufekci in a June 4, 2015, New York Times Op-Ed entitled, "Mark Zuckerberg, Let Me Pay for Facebook." Tufekci cites an August 2014 article in The Atlantic by Ethan Zuckerman that determined the profit Facebook makes from each user per month: 20 cents. Consider the average Facebook user spends 20 hours a month using the service. Tufekci points out that very few Facebook users (or Google users or Yahoo users, etc.) would object to paying 20 cents a month to use the service without ads, without tracking, and with encryption and other data protections. After all, no one appreciates privacy more than Mark Zuckerberg -- the guy who spent $30 million to buy the homes surrounding his residence in Palo Alto, CA, and more than $100 million for land in Hawaii noted primarily for its seclusion. Hey, Zucky baby, hows about showing your "customers" a little respect? |