Menu

Now you can really lock your phone

iOS 8 appears to be a slow-starter. That's not a big surprise. Still, there's one new security feature in particular that makes the upgrade worthwhile, though there's no need to rush into it.

CNET's Lance Whitney reports in a September 19, 2014, article that iPhone users aren't upgrading to iOS 8 as quickly as they upgraded to iOS 7. As a general rule, if everything's working okay, there's no need to apply a big upgrade right away. If you wait a few days, you let the early adopters discover any problems that may arise.

One reason iOS 8 will be an essential upgrade for many people is total-control encryption. Apple will no longer be able to decrypt your phone. Without the passcode, your phone's data is inaccessible to anyone -- including law enforcement. (Google plans to do likewise in an upcoming version of the Android OS, as CNET's Steven Musil reports in a September 18, 2014, article.)

Where does that leave someone who has been served a warrant demanding access to the phone's contents? Can the person invoke their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination?

In a September 19, 2014, article, Forbes' Kashmir Hill cites an analysis of warrants for encrypted phones by the Electronic Frontier Foundation's Hanni Fakhoury. In one case, a district court required that the defendant decrypt a computer. In another, a circuit court of appeals ruled the government was prevented by the Fifth Amendment from forcing the defendant to decrypt several computer hard drives. In the former case, the police knew specifically what files they were looking for; in the second, the police merely suspected the computers contained illegal material.

Locking your phone doesn't lock your data completely. It's still available on the computer you used to back it up. And if you use iCloud, Dropbox, or another non-encrypted online storage service, the data can be accessed from those servers.

For example, I use a passcode for my phone, but I don't encrypt most of the data I store online, and I don't encrypt the phone's backup on my computer. The data on my phone seems more vulnerable: I'm more likely to lose my phone than I am to lose my laptop or office PC.

There are many good reasons for using a passcode to protect your phone that have nothing to do with warrants. Still, people should have the legal power to prevent the authorities from accessing their phones without their consent. The government's just going to have to get the data some other way. Difficult, not impossible.

Note that there are also many good reasons for sharing your passcode with at least one person. Practically speaking, if you encrypt your phone, make sure someone besides you knows your passcode -- or would have easy, obvious access to it -- in case of an emergency.

One reason iOS 8 will be an essential upgrade for many people is total-control encryption. Apple will no longer be able to decrypt your phone. Without the passcode, your phone's data is inaccessible to anyone -- including law enforcement. (Google plans to do likewise in an upcoming version of the Android OS, as CNET's Steven Musil reports in a September 18, 2014, article.)

Where does that leave someone who has been served a warrant demanding access to the phone's contents? Can the person invoke their Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination?

In a September 19, 2014, article, Forbes' Kashmir Hill cites an analysis of warrants for encrypted phones by the Electronic Frontier Foundation's Hanni Fakhoury. In one case, a district court required that the defendant decrypt a computer. In another, a circuit court of appeals ruled the government was prevented by the Fifth Amendment from forcing the defendant to decrypt several computer hard drives. In the former case, the police knew specifically what files they were looking for; in the second, the police merely suspected the computers contained illegal material.

Locking your phone doesn't lock your data completely. It's still available on the computer you used to back it up. And if you use iCloud, Dropbox, or another non-encrypted online storage service, the data can be accessed from those servers.

For example, I use a passcode for my phone, but I don't encrypt most of the data I store online, and I don't encrypt the phone's backup on my computer. The data on my phone seems more vulnerable: I'm more likely to lose my phone than I am to lose my laptop or office PC.

There are many good reasons for using a passcode to protect your phone that have nothing to do with warrants. Still, people should have the legal power to prevent the authorities from accessing their phones without their consent. The government's just going to have to get the data some other way. Difficult, not impossible.

Note that there are also many good reasons for sharing your passcode with at least one person. Practically speaking, if you encrypt your phone, make sure someone besides you knows your passcode -- or would have easy, obvious access to it -- in case of an emergency.

Me and My Shadow pinpoints the information you're sharing, and how you're sharing it

Tracking is everywhere. Trying not to be tracked is more trouble than it's worth. That appears to be the prevailing sentiment. What the data analyzers can do with what they know about us isn't scary enough -- yet.

If you're curious about what personal information is leaking from your computers, phones, Internet connection, and web services, visit Me and My Shadow, a free site offered by the Tactical Technology Collective. When I used the site's Trace My Shadow tool, it identified "at least" 122 personal-information shares.

It would be nice to have a "Stop Sharing" button you could click that would apply to all shares -- or at least those that aren't necessary for your machines, devices, and apps to run correctly. Me and My Shadow provides plenty of information about free services that help you restrict the amount of personal information you share, including Better Privacy, AdBlock Plus, Privacy Badger, and Lightbeam. (In a May 7, 2013, article I described three essential security add-ons for Firefox, Chrome, and IE.)

Guesstimating the number of government requests to ISPs for personal info

Much attention is being paid to the transparency reports issue regularly by Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook, and other Internet services. In a September 16, 2014, article on Vice, Joseph Cox points out the imprecision of the reports, which include ranges of requests or accounts affected, such as "0-999" or "15,000-15,999."

When you look at the big picture delivered by the reports, it's that government requests affect very few accounts. For example, Dropbox's transparency report indicates the service received between 0 and 249 government requests, which affected between 0 and 249 accounts. Considering the 300 million total Dropbox users, that would represent a little drop in the big bucket. (The number of Dropbox users is quoted by Cox from a September 15, 2014, article in the Guardian.)

Still, when it comes to online privacy, it's safest to assume there's no such thing.

Tracking is everywhere. Trying not to be tracked is more trouble than it's worth. That appears to be the prevailing sentiment. What the data analyzers can do with what they know about us isn't scary enough -- yet.

If you're curious about what personal information is leaking from your computers, phones, Internet connection, and web services, visit Me and My Shadow, a free site offered by the Tactical Technology Collective. When I used the site's Trace My Shadow tool, it identified "at least" 122 personal-information shares.

It would be nice to have a "Stop Sharing" button you could click that would apply to all shares -- or at least those that aren't necessary for your machines, devices, and apps to run correctly. Me and My Shadow provides plenty of information about free services that help you restrict the amount of personal information you share, including Better Privacy, AdBlock Plus, Privacy Badger, and Lightbeam. (In a May 7, 2013, article I described three essential security add-ons for Firefox, Chrome, and IE.)

Guesstimating the number of government requests to ISPs for personal info

Much attention is being paid to the transparency reports issue regularly by Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook, and other Internet services. In a September 16, 2014, article on Vice, Joseph Cox points out the imprecision of the reports, which include ranges of requests or accounts affected, such as "0-999" or "15,000-15,999."

When you look at the big picture delivered by the reports, it's that government requests affect very few accounts. For example, Dropbox's transparency report indicates the service received between 0 and 249 government requests, which affected between 0 and 249 accounts. Considering the 300 million total Dropbox users, that would represent a little drop in the big bucket. (The number of Dropbox users is quoted by Cox from a September 15, 2014, article in the Guardian.)

Still, when it comes to online privacy, it's safest to assume there's no such thing.

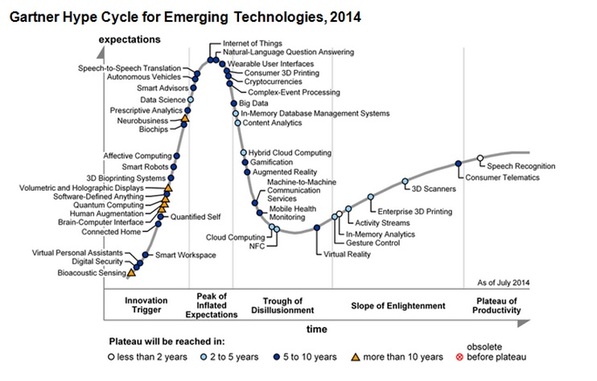

The Hype Chart: New technologies' long, slow ride to acceptance

The 2014 edition of the Gartner Hype Cycle for Emerging Technologies separates the hokum from the real deals in a single, easy-to-decipher infographic. It's looking good for speech recognition and consumer telematics, but if you're waiting for brain-computer interfaces and bioacoustic sensing to go mainstream, well, don't hold your breath.

The chart indicates that cloud computing is just entering the "Trough of Disillusionment" and is still two to five years from reaching the "Plateau of Productivity," a.k.a. tech nirvana. I don't know if that's the good news or the bad news, both, or neither.

One thing that gives the graphic instant credibility in my book is the placement of the Internet of Things at the "Peak of Inflated Expectations." You won't find me among the Cult of (id)IoTs -- at least not for another five to ten years.

The 2014 edition of the Gartner Hype Cycle for Emerging Technologies separates the hokum from the real deals in a single, easy-to-decipher infographic. It's looking good for speech recognition and consumer telematics, but if you're waiting for brain-computer interfaces and bioacoustic sensing to go mainstream, well, don't hold your breath.

The chart indicates that cloud computing is just entering the "Trough of Disillusionment" and is still two to five years from reaching the "Plateau of Productivity," a.k.a. tech nirvana. I don't know if that's the good news or the bad news, both, or neither.

One thing that gives the graphic instant credibility in my book is the placement of the Internet of Things at the "Peak of Inflated Expectations." You won't find me among the Cult of (id)IoTs -- at least not for another five to ten years.