Menu

iPhone's new Medical ID feature could save your life

The kinks appear to be worked out of iOS 8, currently at version 8.02. I upgraded an iPhone 5 and an iPhone 5c with only a minor hiccup when the iPhone 5 was unable to sign into iCloud. An unscheduled restart completed the update.

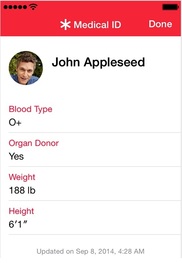

The first feature I enabled after completing the upgrade on both phones was the new Health app's Medical ID card that lets you enter emergency information that can be accessed from the lock screen. This is a potential life-saver.

Whenever sensitive personal information is being collected and shared, there's a tradeoff between privacy and utility. The iPhone's Health app has the potential to create a detailed medical profile that could compromise your privacy and make you more vulnerable to an attack by cyber-criminals. It's natural for questions to arise about the risks entailed in sharing private health information.

However, Medical ID's potential in the event of an emergency makes it well worth any possible loss of privacy. This is particularly true for people with allergies to medications or other life-threatening conditions, but it also comes in handy for someone who finds your lost phone and wants to return it to you. The emergency screen lets you share as much or as little information as you choose.

The first feature I enabled after completing the upgrade on both phones was the new Health app's Medical ID card that lets you enter emergency information that can be accessed from the lock screen. This is a potential life-saver.

Whenever sensitive personal information is being collected and shared, there's a tradeoff between privacy and utility. The iPhone's Health app has the potential to create a detailed medical profile that could compromise your privacy and make you more vulnerable to an attack by cyber-criminals. It's natural for questions to arise about the risks entailed in sharing private health information.

However, Medical ID's potential in the event of an emergency makes it well worth any possible loss of privacy. This is particularly true for people with allergies to medications or other life-threatening conditions, but it also comes in handy for someone who finds your lost phone and wants to return it to you. The emergency screen lets you share as much or as little information as you choose.

In his overview of the new features in iOS 8, Tim Bradshaw of the Financial Times points out that Apple is restricting how third parties can use the personal health data they collect. The new version also reminds you regularly of apps that are sharing your location so you can consider whether they need to do so. Of course, if the reminders become too obtrusive, people are more likely to click through all such pop-ups automatically and could thus fall victim to a malware attack.

(There's also the question of inadvertent tracking. ZDNet's James Kendrick discovered that his new iPhone 6 had automatically tracked his walking distance since he first activated the phone.)

(There's also the question of inadvertent tracking. ZDNet's James Kendrick discovered that his new iPhone 6 had automatically tracked his walking distance since he first activated the phone.)

Decide how much information you want to share with the world

Start by opening the heart-shaped Health app that the update installs by default. The four options are Dashboard, Health Data, Sources, and Medical ID. The screens are shown on the Apple Support site. Dashboard and Health Data entail relatively long-term projects and considerable personal data collection. The Sources component is intended for third-party apps and devices, which likely will collect even more personal information. (9 to 5 Mac's Jordan Kahn describes iHealth's nine iPhone-connected healthcare accessories.)

The only feature I'm interested in at the moment is the fourth one in the list at the bottom of the screen: Medical ID. This option activates the Emergency link that appears on the bottom-left corner of the lock screen (as shown in the first screen above).

When you press Medical ID, the next unlock screen has a Medical ID option in the bottom-left corner of the "Emergency call" screen (as shown in the second screen above).

Press it to open the Medical ID information you supplied in the Health app (as shown in the third screen above).

MacUser's Caitlin McGarry describes how hospitals will be using iOS 8's HealthKit tools in test projects. For example, Stanford University Hospital plans to use HealthKit to track blood sugar levels in diabetic children.

The HealthKit's goal is to remove human error from health-data collection because you don't rely on the patient or someone else to record and report the information accurately. the accuracy and reliability of the data collected by HealthKit apps and devices is yet to be determined, but their potential is undeniable.

Double Randomnity: Four items in malarrayed disevalence

Mobile data collection for the public good? At least one study indicates that aggregate mobile-phone data could help predict high-crime areas. (pdf) Then again, you could just ask the cabbies.

An oncologist named Paolo G. Casali wrote an article in the Parliament Magazine in which he pleads for the European Union not to enact proposed regulations that would restrict access to health information by cancer researchers. The European Society of Medical Oncology objects to two requirements: re-consent each time data or tissues are reused; and requiring consent to use patient data in population-based cancer registries, which generally cover broad areas and have only generic personal information.

As with Europe's misguided attempt to enforce a right to be forgotten despite online being forever, there's careful and there's too careful and there's shooting yourself in the foot.

From the north, a sign of hope for authentication that doesn't depend on passwords. As I wrote in an August 18, 2014, article, stolen or compromised user IDs and passwords are the cause of nearly all data breaches. Now a Canadian company named Bionym is developing a wristband it claims will identify you based on your heartbeat.

The Nymi bracelet has an electrocardiogram sensor that verifies your identity by monitoring your unique heart rhythm. The sensor doesn't record your heart rate the way a standard EKG machine does. Instead, it tracks the electrical activity generated by your heart.

In addition to authenticating you to computers and devices, the company claims the Nymi can be used to unlock doors and activate devices automatically in the future Internet-of-Things universe. But why stop at a wristband? The potential anatomical adjuncts are limitless! A connected earpiece, a cloud necklace, an Internet of Things ring, a really smart pair of glasses (minus the camera and other creepiness of Google Glass).

Which body-accoutrement authenticator would you prefer?

Law enforcement is crying foul over iOS 8's encryption, which Apple claims can be decoded only by you. On the Huffington Post, Igor Bobic and Ryan J. Reilly report on FBI Director James Comey's objections to Apple's plans.

Last week's Weekly pointed out that there are many other sources for the information, so the government would simply have to work a little harder to get it. Micah Lee explains on the Intercept that Apple's claims about the iPhone's data protections may be overstated.

First of all, iCloud storage and backups on Mac or PC either aren't encrypted or use encryption that Apple can decrypt. Also, four-digit passcodes are susceptible to brute-force attacks, and the fingerprint scanner found on some iPhone models can be bypassed. Lastly, video and audio recordings may not be encrypted: they weren't previously, and Lee states that Apple didn't respond to a request for comment on that matter.

The consensus appears to be that iOS 8's unbreakable encryption is part legitimate, part hyperbole. Apple can now claim to be unable to decrypt an iPhone's data, and the government has to look elsewhere for the information they need to prosecute crimes. But is your data absolutely, positively inaccessible to anyone but you? Don't bet on it.

Start by opening the heart-shaped Health app that the update installs by default. The four options are Dashboard, Health Data, Sources, and Medical ID. The screens are shown on the Apple Support site. Dashboard and Health Data entail relatively long-term projects and considerable personal data collection. The Sources component is intended for third-party apps and devices, which likely will collect even more personal information. (9 to 5 Mac's Jordan Kahn describes iHealth's nine iPhone-connected healthcare accessories.)

The only feature I'm interested in at the moment is the fourth one in the list at the bottom of the screen: Medical ID. This option activates the Emergency link that appears on the bottom-left corner of the lock screen (as shown in the first screen above).

When you press Medical ID, the next unlock screen has a Medical ID option in the bottom-left corner of the "Emergency call" screen (as shown in the second screen above).

Press it to open the Medical ID information you supplied in the Health app (as shown in the third screen above).

MacUser's Caitlin McGarry describes how hospitals will be using iOS 8's HealthKit tools in test projects. For example, Stanford University Hospital plans to use HealthKit to track blood sugar levels in diabetic children.

The HealthKit's goal is to remove human error from health-data collection because you don't rely on the patient or someone else to record and report the information accurately. the accuracy and reliability of the data collected by HealthKit apps and devices is yet to be determined, but their potential is undeniable.

Double Randomnity: Four items in malarrayed disevalence

Mobile data collection for the public good? At least one study indicates that aggregate mobile-phone data could help predict high-crime areas. (pdf) Then again, you could just ask the cabbies.

An oncologist named Paolo G. Casali wrote an article in the Parliament Magazine in which he pleads for the European Union not to enact proposed regulations that would restrict access to health information by cancer researchers. The European Society of Medical Oncology objects to two requirements: re-consent each time data or tissues are reused; and requiring consent to use patient data in population-based cancer registries, which generally cover broad areas and have only generic personal information.

As with Europe's misguided attempt to enforce a right to be forgotten despite online being forever, there's careful and there's too careful and there's shooting yourself in the foot.

From the north, a sign of hope for authentication that doesn't depend on passwords. As I wrote in an August 18, 2014, article, stolen or compromised user IDs and passwords are the cause of nearly all data breaches. Now a Canadian company named Bionym is developing a wristband it claims will identify you based on your heartbeat.

The Nymi bracelet has an electrocardiogram sensor that verifies your identity by monitoring your unique heart rhythm. The sensor doesn't record your heart rate the way a standard EKG machine does. Instead, it tracks the electrical activity generated by your heart.

In addition to authenticating you to computers and devices, the company claims the Nymi can be used to unlock doors and activate devices automatically in the future Internet-of-Things universe. But why stop at a wristband? The potential anatomical adjuncts are limitless! A connected earpiece, a cloud necklace, an Internet of Things ring, a really smart pair of glasses (minus the camera and other creepiness of Google Glass).

Which body-accoutrement authenticator would you prefer?

Law enforcement is crying foul over iOS 8's encryption, which Apple claims can be decoded only by you. On the Huffington Post, Igor Bobic and Ryan J. Reilly report on FBI Director James Comey's objections to Apple's plans.

Last week's Weekly pointed out that there are many other sources for the information, so the government would simply have to work a little harder to get it. Micah Lee explains on the Intercept that Apple's claims about the iPhone's data protections may be overstated.

First of all, iCloud storage and backups on Mac or PC either aren't encrypted or use encryption that Apple can decrypt. Also, four-digit passcodes are susceptible to brute-force attacks, and the fingerprint scanner found on some iPhone models can be bypassed. Lastly, video and audio recordings may not be encrypted: they weren't previously, and Lee states that Apple didn't respond to a request for comment on that matter.

The consensus appears to be that iOS 8's unbreakable encryption is part legitimate, part hyperbole. Apple can now claim to be unable to decrypt an iPhone's data, and the government has to look elsewhere for the information they need to prosecute crimes. But is your data absolutely, positively inaccessible to anyone but you? Don't bet on it.