Menu

Do we have a right to know what they know about us? |

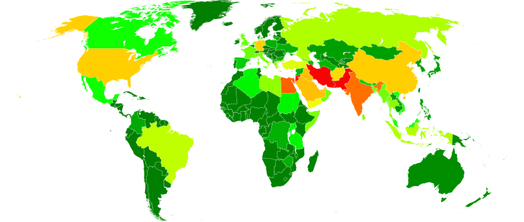

World surveillance map: Green (little), Yellow (some), Orange (much), Red (most). Credit: Rezonansowy - Own work This file was derived from: BlankMap-World6.svg (click to enlarge) World surveillance map: Green (little), Yellow (some), Orange (much), Red (most). Credit: Rezonansowy - Own work This file was derived from: BlankMap-World6.svg (click to enlarge)

We're followed around the web -- there's nothing new about that. We're tracked in the real world, too. That's not always a bad thing, as Jimmy Hubert will tell you. Hubert is the Georgia Tech student who went missing and was found face-down in a ditch by two friends. The friends used Hubert's Find My iPhone app to locate the remote area where Hubert's phone lost power. Their discovery of their friend near that spot is recounted in a report by KSB TV in Atlanta.

It gets creepy when you realize the algorithms the data collectors apply to their data oceans can extrapolate what we’re thinking and feeling based on their analysis of our activities. Even if you're one of the many people who are unconcerned about being surveilled, you may be curious to know what Facebook, Google, Amazon, Apple, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, and other data-collecting services know about you. The same goes for the personal dossiers collected, maintained, and often sold by government agencies large and small. In the May 5, 2015, Weekly I wrote about big data's potential to serve the public good. You have to keep the data safe yet accessible, and the data collection has to be legal, which means the people who are the source of the data (us) gave knowing and voluntary consent. (Along these lines, a big "hurray!" for California’s new digital privacy law, which Wired’s Kim Zetter reports on in an October 8, 2015, article.) The question is, do we have a right to know what the personal data collectors know about us? The collectors say “no.” I say “yes.” California’s ‘Right to Know’ proposal goes nowhere fast In a May 6, 2013, article, The Verge’s Jeff Blagdon describes the fate of Right to Know Act of 2013, which was proposed by former Assembly member Bonnie Lowenthal, D-Long Beach. The bill would have allowed Californians to ask businesses what information they have collected about them as customers, and who the organizations are sharing the information with. The ACLU supported the proposal, but tech firms objected. TechAmerica and other industry groups representing the Internet giants called the bill “unworkable” and claimed it misunderstood the way the Internet works. As Blagdon points out, the ACLU counters these assertions by pointing to the thriving market for personal information, and the increasing number and severity of data breaches. When she withdrew the bill in 2013, Lowenthal was confident it or a similar proposal would be enacted in the next Assembly session in 2014, but that didn’t happen. (Lowenthal was forced out of the Assembly by term limits in 2014.) In an October 4, 2015, article in the Marin Independent-Journal, Thomas Peele explains that California’s public-records laws are designed to allow government officials to keep secret anything they want to keep secret. In the officials’ minds, the public has no right to know anything the officials don’t want them to know. For example, if an open-records request is rejected in California, the only way to appeal the decision is to “sue and hope to recover fees,” according to Peele. He points out that the federal Freedom of Information Act has just as many loopholes and hurdles that serve to prevent disclosure of public documents. In effect, government agencies are allowed to act with no oversight whatsoever. Are you feeling safer yet? The threats posed by uneven distribution of personal information The day I stopped betting on horse races was the day I realized there would always be a handful of people who had much more information about the horses in the field and other aspects of the race than I had – or could ever hope to have unless I somehow got access to their inner circle. Information is power, and power is money. They have more information, so they have an edge over the rest of the parimutuel pool. Now it’s the companies and government agencies we deal with that have the information edge. You can expect them to use this edge to their advantage -- perhaps to our disadvantage. They’re understandably loathe to let go of that edge. Maybe they would be willing to make the data collection more transparent by letting us know what data they're collecting about us, and what they're doing with that data. The long, slow slog to full data disclosures and an open government I'm betting that it will happen. Not tomorrow, not next year, but someday we will establish a right to know what the organizations that collect and profit from our personal information know about us. One principle that may unlock some of our personal data is a novel application of the right of publicity, which is also called personality rights. According to Cornell University’s Legal Information Institute, the right of publicity “prevents the unauthorized commercial use of an individual's name, likeness, or other recognizable aspects of one's persona.” It states further that the right “gives an individual the exclusive right to license the use of their identity for commercial promotion.” This right usually falls under the umbrella of the right to privacy. For example, the tort of invasion of privacy has four types, according to the Restatement (Second) of Torts, § 652C: intrusion, appropriation of name or likeness, unreasonable publicity, and false light. You might think the right of publicity would fall under the “unreasonable publicity” category, but courts have ruled that it relates more to unauthorized appropriation of name or likeness. ‘Your identity has value’ The Legal Information Institute examines all federal laws relating to the collection and disclosure of personal information, but it points out that the FTC’s guidelines in this area are voluntary, and are routinely ignored by the data collectors. While the right of publicity applies to the commercial value of a person’s name and likeness, the right isn’t just for celebrities anymore. As Lori Levine, Kimberly L. Buffington, and Carolyn S. Toto write in an October 7, 2015, article on Lexology, “[y]our identity has value.” The example the Lexology authors provide is Perkins v. LinkedIn Corp., 53 F. Supp. 3d 1222 - Dist. Court, ND California 2014, in which the plaintiffs assert that LinkedIn used their names and likenesses to induce the people in their contacts list to join the service, sending them multiple emails stating that “So-and-so sent you an invitation to join their professional network at LinkedIn.” The court ruled that LinkedIn did not acquire the users’ consent to send subsequent emails to the contacts; their broad consent to LinkedIn’s terms of service applied only to the initial email to the contacts. The authors point out that social media services could simply rewrite their terms of service and alter their disclosure policy to preclude a right of publicity suit by users. This strategy works only if the courts are convinced the services have acquired informed consent for their use of customers’ personal information. I would argue that you can’t consent knowingly and voluntarily until you know what the heck it is you are consenting to. What information are you collecting? How are you using it? Who are you sharing it with? What are you doing to prevent it from falling into the wrong hands? There is no informed consent to the collection and use of our personal information. And there won’t be until the data collectors inform us of what they’re up to. That won’t happen until the law requires it. And the law won’t require it until we tell our lawmakers that we refuse to waive our right to know. |