Menu

Simple ways to limit the private information you surrender on the web

|

Image credit: Sherbit Image credit: Sherbit

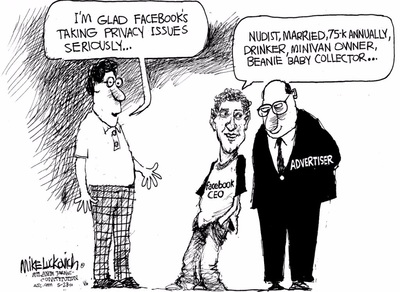

Governments and businesses collect our personal information to an extent we can’t even fathom. They are profiting exorbitantly from this asset, which they acquire without having to gain consent, nor do they fairly compensate the valuable asset’s source: us.

The data about us is collected all day, every day, without anything resembling informed consent. We don’t know what’s collected, who’s collecting it, who’s using it, how they’re profiting, or how it used against our best interests. Do we really have a choice whether to use services that scoop up our personal information in exchange for a “free” account? In many cases, we do. Julia Angwin is an investigative journalist for ProPublica. She recently accepted the challenge of avoiding as many privacy-invading web services as she could. Angwin writes about her successes in a September 20, 2016, article on Consumer Reports. She found that the steps required to protect her privacy were “simple, cheap, and effective,” and easy enough for anyone to adopt, for the most part. The added bonus is that the process made Angwin feel like she was in charge of “locking the door on my digital home.” Gain privacy, plus a lot of extra time Privacy protections begin with your browser security settings, which have to be adjusted from the defaults to block third-party cookies, for example. I explain this and other option changes for Firefox, Chrome, and IE in the June 24, 2014, Weekly. Two other security steps Angwin takes are to use a password manager, and to put a piece of tape over the camera above her laptop’s screen. Not everyone will follow Angwin’s lead in taking the next step, which is ditching LinkedIn and Facebook. Personally, I haven’t signed into my LinkedIn account in many months, and I have no plans to do so anytime soon. My Facebook use has ebbed, although I sign in for 10 or 15 minutes at a time every other day or so. I’m ready to take Angwin’s advice and rely on my wife to alert me to new pictures of the grandkids, which is really what Facebook is best at. The next big-name services to get the boot from Angwin are Google’s search and email offerings. It’s true that, as Angwin writes, “Google had more intimate information about me than my closest friends and family.” (View your profile by going to the account’s privacy dashboard.) Instead of Google, Angwin uses DuckDuckGo for searches, and she created her own $200 “encrypted cloud storage system” for her email. Obviously, the former’s quite a bit easier than the latter. Years ago I attempted to switch from Gmail. In “Ten simple, common-sense security tips” from October 9, 2012, I describe how to send and receive mail from your Gmail account without having to be signed into Google. It worked okay for a while, but, I’ve been using the same Gmail address since the service was in private beta, so that extensive history works for me as well as for Google. Soon after Inbox was released, I switched back to staying signed into my Google account. That doesn’t prevent me from using other more-private email accounts and search services on a regular basis. DuckDuckGo is one of several search services that promise not to maintain a history of your searches or track you in any other way. Another is StartPage, which calls itself “the world’s most private search engine.” Gizmo’s Freeware provides an extensive guide to the “Best free anonymous surfing services.” Plenty of legit reasons for creating an alter ego Another of Angwin’s steps that not all privacy lovers are willing to take is to create a pseudonym and a false profile to go along with it. Angwin adopted the persona of Ida Tarbull, “a turn-of-the-century muckracker.” So long as you’re not doing so for fraud, it’s completely legit to go all double-naught spy, up to and including what Angwin devised in Ms. Tarbull’s name: “a credit card (linked to my account), an email address, an Amazon account, a postal address, a cell phone, and even a few social media accounts.” The point of concocting such a made-up identity isn’t to be untrackable. Angwin points out that it would have been easy for anyone to connect her to the pseudo-persona using the most basic detective skills. For Angwin and others, the reward is in knowing you’re able to purchase a silly app or a box of dark-chocolate-covered almonds without sharing the information with the world. Angwin concludes that these privacy-protecting measures are required only because people in the U.S. don’t benefit from the same safeguards available to European residents. In Europe, any company that collects personal information must give the person access to the data, the ability to dispute it, and often the right to have it removed from the services’ databases. Even with all of her efforts to keep her private information private, Angwin admits that she’s still being profiled quite a bit. The experiment was a success because it allowed her to take control over a big chunk of the technology in her life. It also renewed her hope that her children will be free of such tracking as they become adults. Dusting off the Privacy Manifesto Way back about four years ago, I wrote a paper for school entitled “Reclaim your personal information,” which included what I boldly proclaimed was a Privacy Manifesto. I remember well the reaction of my professor after she read it: “Good luck with that.” Translation: “You’re dumber than you look, and that’s saying something. Plus, your momma dresses you funny.” I’ll have the professor know that I am fully capable of dressing myself funny all by myself. Also, I’m not the only one making those valiant proclamations about people owning their personal information and having the legal right to control it. The Guardian’s Jathan Sadowski writes in an August 31, 2016, article that “data appropriation is a form of exploitation.” Even if you buy the argument that we exchange our personal information for use of a service such as Google or Facebook (and I’m one who doesn’t buy it), that doesn’t account for the many, many, many businesses that profit from much of the very same information without giving you a darned thing, and in fact they deprive you of the value you may otherwise be able to get for the information. If all companies are now tech companies, as they say, then all companies now are in the business of collecting, selling, buying, and otherwise getting their hands on our private information: who we are, what we do, when we do it, where we go, even what we’re thinking. (The government’s doing the same thing, but that kettle of fish will have to wait for another Weekly.) Sadowski argues that companies create value from the data without providing just compensation. He concludes that by framing the data appropriation as theft, it becomes a legal issue and is subject to legal protections against the “new class of robber barons” that was spawned by the “Gilded Age 2.0.” All I know is, people are getting taken advantage of, big time, and nobody’s doing a damn thing about it. This here squirrel-cage operation can’t do much to change that, but it’ll keep squeaking for as many Weeklys as it can churn out. |