Menu

Trust Busters 2.0: Dismantling modern monopolies |

So much for competition.

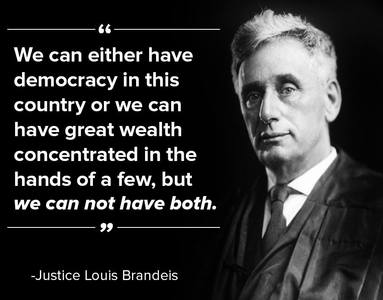

Four companies account for nearly all of the cable and internet service in the U.S. There are also four airlines, four banks, and four internet giants: Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Apple. As the Nation's David Dayen writes in an April 4, 2017, article, consolidation is everywhere: agriculture, entertainment, retail, even toothpaste (two major players) and sunglasses (Luxottica holds a true monopoly). In addition to limiting consumer choice, monopolies centralize both political power and economic power. Creativity suffers because the incentive to innovate diminishes as barriers to entry enlarge. To no one's surprise, monopolies exacerbate inequality by rewarding the few at the top, at the expense of the many below them. Dayen claims the cause of the return to the bad-old days is the rise of the "Chicago school" starting in the Reagan era. The purpose of anti-trust regulation was transformed from preventing centralization of power to "consumer welfare." The likes of Robert Bork and other corporate shills argued that so long as consumer prices were low, centralized power was good for everybody. The dawning of the 'New Brandeis movement' In response to the massive consolidation of economic and political power, a group of economists are working to "revive the Progressive Era conception of monopoly as a danger to American liberty," according to Dayen, who refers to them as the "New Brandeis movement." Before becoming a member of the U.S. Supreme Court, Louis Brandeis was an advisor to President Woodrow Wilson, who strengthened anti-trust rules and created the Federal Trade Commission. Brandeis wrote, “We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.” The threats monopolies pose to democracy were the topic of a recent conference in Chicago, ironically, entitled “Does America Have a Concentration Problem?” An example is what one researcher calls "Amazon's Antitrust Paradox": Amazon uses customer data collected by the companies on the Amazon platform to compete against those very companies. Undoing 35 years of influence on political and economic thinking promises to be a long, hard road. Dayen writes that simply introducing a counter-argument forces the power elite in the three branches of government to respond, if only to defend their long-entrenched positions. --------------------------------------------------- Busting the myth of single-digit unemployment rates Sometimes a statistic just jumps right up and bites you. Here's one for you: 59 percent. That's the Economist's measure of the labor-force participation of white working-class males in the U.S. Conversely, 41 percent of white working-class males who are able to work are unemployed. The labor-force participation rate for all workers is 69 percent, which is down considerably from the 87-percent rate recorded in 1948. These numbers came to mind when I read the March 30, 2017, Medium post by Travis Lowe describing life in a poor Appalachian town. The downward spiral began in the 1980s as coal jobs disappeared and housing values plunged. In McDowell County, 90 percent of school children are below the poverty threshold for free meals, 47 percent of children do not live with their biological parents, and 77 percent of children live in a household where no one has a job. Lowe points out that when a person's job is taken from them, they lose more than an income. Much of a person's identity comes from their work. Their sense of obligation to the community often is derived from their job. In addition to losing financial security, a person forfeits a part of their social identity, according to Lowe. The silver lining to these dark clouds is a revived sense of community as locals depend increasingly on each other to survive. Lowe writes that neighbors look out for neighbors, government workers cooperate across administrative boundaries, professionals spend more time volunteering to help individuals and the entire community. The topper is that more than 100 local business owners have joined together to transact with each other as much as possible to keep their money flowing through the community. Lowe argues that the people of Appalachia are the experts when it comes to crafting solutions to a world without jobs. --------------------------------------------------- A better approach to protecting consumers from misuse of anonymized private data The internet services that collect our private data dismiss concerns about misuse of the information with a single promise: "We anonymize it." A paper (pdf) by researchers Sophie Stalla-Bourdillon and Alison Knight takes a look at anonymization as it relates to meeting European Union privacy requirements. Two problems in particular were highlighted by the researchers:

The source of both problems is the static approach vendors and regulators take toward data anonymization. They mistakenly believe that once the data has been anonymized, it will never revert to being traceable to the source, and therefore be private once again. Anonymized data is outside the scope of EU data-privacy regulations. If the recipient of the anonymized information doesn't have access to the "raw" data sets, the third party isn't subject to privacy protections. The researchers suggest an approach: Whether the party using the data has a duty to protect it depends on the context of the use. For example, if a researcher is using the data for a non-commercial or public purpose, the risk of misuse of the data is low, so the duty to protect would be low. By contrast, if the third party has a commercial purpose for using the information, there's a greater risk the data could be applied against our best interests or otherwise misused. Therefore, commercial data brokers would need to meet a higher duty to protect the data from abuse. At the same time, the original compiler of the personal information would continue to owe a duty to the sources of the data to ensure the people behind the data are not put at greater risk as a result of the commercialization of their private information. That would sure beat the protections in place now, which are, like, none. |