Menu

|

The appropriate response to living in a surveillance state: Ignore it

|

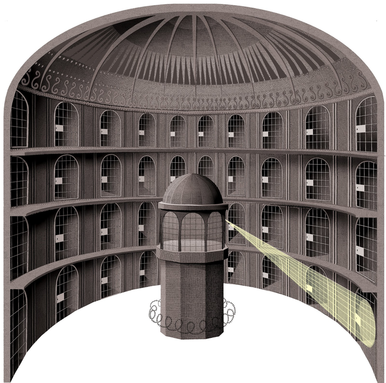

So there’s this thing called a panopticon. It was originally devised by a Briton named Jeremy Bentham who lived in the late 18th century and fancied himself a social reformer. He envisioned a prison in which the inmates were constantly monitored by a central, invisible authority who occupied a place in the middle of the open space in which the prisoners lived. The inmates weren’t certain when, or even if, the authority was looking at them, so they acted as if they were always under surveillance.

Well, no such prison has ever been built successfully, and all attempts in the past to create a panopticon – in Tsarist Russia and 1920’s Cuba, most notably – have failed. The concept was revived in the 1970s by French philosopher Michel Foucault, who proposed in his book Discipline and Punishment that the panopticon principles could be applied to a “disciplinary society” by creating “a consciousness of permanent visibility as a form of power, where no bars, chains, and heavy locks are necessary for domination any more.” Foucault claimed that all modern hierarchical structures have evolved into panopticons – the military, schools, hospitals, and most notably, workplaces. The key result of people believing they are under constant surveillance is a chilling effect on their behavior. We conform not only to socially acceptable acts, but also to socially acceptable thoughts – at least those thoughts that are overtly expressed. Some people have attempted to extend the panopticon metaphor to digital surveillance conducted by government, ostensibly for security purposes; and by private companies for marketing purposes. The comparison is strained by a couple of factors, the most important is that most people either aren’t aware of the digital surveillance, or they know about it but simply don’t consider the activity a threat. As the Guardian’s Thomas McMullan writes in a July 23, 2015, article, there’s a big difference between surveillance of our physical selves and surveillance of our personal information. Even post-Snowden, few people are concerned that their online activities are being watched. McMullan points out that the aura of Internet anonymity persists in the face of much evidence to the contrary. The catch is that the Internet of Things is bringing our physical selves back into the surveillance equation. Everything from heart-rate monitors to ubiquitous GPS devices serve up detailed information disclosing who we are, what we are, how we are, and where we are. From this information it becomes much easier to extrapolate what we’re thinking. McMullan points out that Bentham did not intend the panopticon to serve as a “tool for oppression” but rather as a way to promote health, morality, and “industry.” After failed panopticon experiments, Bentham became an outspoken critic of the concept. In the real world, whoever is in power will serve as the invisible surveillor ready to correct whatever the rulers consider aberrant behaviors. Now turn the equation around and imagine the people are the invisible surveillors and the government is the surveillee. As McMullan writes, “transparency holds power to account.” (The December 2, 2015, Weekly described the potential benefits to society of treating all government data as an open, public resource.) Beware the dangers of the social-media panopticon You know we have come to a sorry pass when we read criticisms of Santa Claus as a fascist because he sees us when we’re sleeping, he knows when we’re awake, he knows whether we’ve been bad or good, and he keeps a list of who’s naughty and who’s nice. Okay, maybe those critics have their tongues planted firmly in their cheeks, but the Elf on the Shelf isn’t getting the same benefit of the doubt from many people. One of those people is Laura Pinto, a researcher at the University of Ontario Institute of Technology. Stephanie Pappas writes in a December 11, 2015, article on Live Science that the Elf is a spy for Santa, one that children aren’t allowed to interact with or even touch, unlike the Bearded One himself, who kids write letters to and visit in person at the mall. Another criticism of the Elf is that he encourages good behavior by promising presents on Christmas morning rather than simply because it’s the right thing to do. In this regard, the Elf is no different than his boss, who threatens little malefactors with the prospect of nothing but coal-filled stockings on Christmas morning. Yes, it is likely these critics are taking a new Christmas tradition a mite too seriously. After all, Santa and his employee the Elf on the Shelf are not actually watching anyone. You can’t say the same about the public and private entities that do collect and analyze information about our digital lives. In an April 8, 2015, article on Open Democracy, Nik Williams reports on a survey by Pen International of fiction and non-fiction writers in countries around the world. The researchers found that 34 percent of writers in so-called free countries had avoided writing or speaking about a particular topic following the Snowden revelations due to concern about government surveillance. The researchers claim self-censorship levels for writers in democratic countries are now on a par with those for writers in totalitarian regimes. It’s not just writers who are self-censoring as a result of the pervasive sense of being watched online. Motherboard’s Alex Pasternack writes in a May 5, 2014, article that searches via Google for terms that appear on the NSA watch list declined precipitously after the Snowden bombshell. I find myself hesitating to list the terms for fear of attracting the wrong kind of attention, but they include such potentially innocuous terms as “fundamentalist” and “hostage.” The government is far from the only entity that affects our online behavior. Social-media shaming sometimes serves as a lawless mob meting out its own misguided sense of justice on anyone who dares breach the mob’s sense of decorum and propriety. In the February 17, 2015, Weekly I wrote about “How to ruin your life in 140 characters or fewer.” You post something stupid, people demonize you, you lose your job, you lose your friends, you pay a price far greater than someone who actually committed a crime. The Nation’s Justin Thomas takes the concept even further in a December 13, 2015, article. Thomas points out that social media have made shaming trivially easy: “Citizen justice unencumbered by due process is quick to condemn and merciless in the pursuit of retribution.” Now the Chinese government is threatening to take shaming to a shameful new level. TechCrunch’s Arthur Chu writes in an October 18, 2015, article about China’s Social Credit System, which pays tech companies to collect financial and personal information about people from social media and other Internet sources, and then boil it down to a numerical rating. Baseless hearsay can cost you a job Chu cites the example of hiring managers readily admitting that they decide against potential hires based solely on negative comments made about the candidates on social networks. He also points to critics of Yelp’s raters, who they refer to as the “Yelp mafia.” Our personal reputations often boil down to whatever appears on the first page of Google results when someone searches our name. What’s to be done? Chu points out that there’s no stopping or even slowing the social-media train, but neither do we need to take whatever information we find on the Internet as gospel. Now more than ever, we need to bring a brimming cupful of skepticism to anything we see on the Web – and I mean everything, even the stuff we put there ourselves. Online is forever, after all. Once you post something, you can’t truly remove it, even if you can no longer find it. That embarrassing photo or half-baked post exists on servers somewhere. We need to be much more tolerant and more forgiving about what others do on social media and elsewhere on the Internet. We all deserve a goodly portion of slack. Save your righteous indignation for the small number of people who truly deserve it. And when you find yourself shying away from expressing a legitimate dissenting or unpopular opinion for fear of an irrational backlash, post on, dude! |