Menu

Cyberwar? Fuhgeddaboudit! There are plenty more serious threats worth fretting over

|

|

Plus: Yahoo makes money selling cute Flickr photos without sharing profits with some of the folks who took the pictures.

|

Did North Korea attack Sony's computers? Not likely.

All evidence points to your plain-old, everyday Internet crooks as the perpetrators of one of the most serious breaches ever to hit a business. Wired's Kim Zetter explains in a December 15, 2014, article that the Sony breach may have begun last February. In the months before word of the breach leaked, the attackers attempted to extort money from Sony by threatening to release the company's confidential information if they weren't paid. As Zetter points out, that's not how nations attack computers. None of the communications received by Sony from the thieves mentions the movie "The Interview" or North Korea. The crooks use two names: "God'sApstls" and "Guardians of Peace." They warned Sony that the private information of its employees would be posted on the Internet unless the employees contacted the group to request that their information be excluded. Sony is attempting to thwart people from downloading the confidential information it lost by setting up "honeypots" that attract people searching for the data and then deflect them. Renowned producer Aaron Sorkin is blaming news organizations that publish any of the stolen information for abetting the theft. Sorkin compares the publication of the private data to the sites that posted the stolen pictures of naked celebrities earlier this year. Sorkin has a point, but there are some differences between the two breaches. The Sony attack entails a threat to send the company into bankruptcy. That's news any day of the week. Also, the leaked information provides an insight into how a big Hollywood company operates. That's news, too. The new reality: You're hacked -- now what? One of the scariest aspects of recent data breaches such as those at Sony, Home Depot, Citibank, and Target are that the thieves were inside the companies' systems for months before they were detected. This makes you wonder how many other breaches never were discovered, or are currently flying under the radar of the victim organization. Chloe Green explains in a November 26, 2014, article on Information Age that companies have to assume their systems have been breached. Organizations have to focus more on locking down their data and less on trying to deny unauthorized access. It's like knowing the crooks are going to get in, but then making sure all the valuables are out of sight and unreachable. How do you do this? Encryption. Why aren't companies encrypting their data already? Because encryption is expensive. It adds to data storage costs, it slows down systems, and it can increase the data-management burden in other ways. Still, what they say about an ounce of prevention applies to a company's sensitive, proprietary information -- in spades. A brief history of cyber warfare The first instance of a computer-based attack by one country against another may have been the 1982 failure of a Siberian oil pipeline. More recently, a Turkish oil pipeline explosion in 2008 is now seen as the result of a cyber attack by Kurdish separatists. As Ars Technica's Dan Goodin points out in a December 10, 2014, article, the first confirmed act of cyber warfare was the 2009 attack on Iran's Natanz nuclear power plant by the Stuxnet worm. Zetter's recently published book, Countdown to Zero Day, describes the digital attack, which took years to prepare and implement. An excerpt from the book highlights the tumult in Iran just prior to the attack as the government quashed protests following a disputed election. It took years for the details of the Stuxnet attack to be revealed, but the press has recently caught a serious case of cyber-war fever. In a December 15, 2014, post on the Wall Street Journal Morning Download blog, Steve Rosenbush reports on the FBI's warning to U.S. businesses about potential attacks by foreign governments -- specifically Iran. Rosenbush even repeats the erroneous claim that North Korea attacked Sony's computers. In another December 15, 2014, post on the UK-based MicroScope site, Simon Quicke warns of a shift toward cyber warfare in 2015. Ars Technica's Goodin writes in a December 10, 2014, article that malware called Inception was created and distributed by some unnamed nation to target the PCs and mobile devices of diplomats. Russian-based security firm Kaspersky Labs claims to have discovered yet another espionage malware it has dubbed Cloud Atlas. This attack is said to be a variant of the earlier Red October malware. The clear and present danger: Internet crooks Computer-based attacks on the U.S. power grid, communication networks, and transportation systems are a distinct possibility. Lax security, such as leaving built-in access controls at their default settings, makes such operations more likely to succeed, as eWeek's Robert Lemos reported in a July 10, 2014, article. On November 17, 2014, NPR's Terry Gross interviewed author Shane Harris, whose book "@War" details what Harris calls the "rise of the military Internet complex." According to Harris, the U.S. intelligence services are working with Google, Facebook, Yahoo, and other major Internet services to "dominate cyberspace and use it to spy on other countries." In a December 4, 2014, post, Quartz's Leo Marini argues that the growing cyberwar hype actually makes countries more vulnerable to attack. Add the prefix "cyber" to any threat and funding magically starts pouring in, according to researchers cited by Marini. The real threat to liberty, the researchers claim, is the militarization of the Internet. That's not to say your average, everyday Internet user isn't at risk. It's just that the real risks we face online are more mundane. The Week's Robert Beckhusen and Matthew Gault argue in a December 3, 2014, post that "America is scared of the wrong things." Topping the list of things Beckhusen and Gault claim we should be concerned about is old-fashioned theft using new-fangled tools. The authors cite numbers from the Bureau of Justice Statistics indicating that 16.6 million U.S. residents were victims of identity theft in 2012. They lost a total of $24.7 billion, which is $10 billion more than the next-highest form of property crime. Simple solutions to thorny security risks So to all you companies concerned about being the next Sony, here are three things you can do to protect yourself: 1) Encrypt your data -- all of it, all the time. 2) Stop relying on user IDs and passwords to authenticate the people who you let access your sensitive data. 3) Force banks to implement chip-based credit cards, which are de rigueur in Europe, or some other payment method that's more secure than today's 1970s-style credit cards. Companies may also want to make sure the third-party vendors they allow to join their networks are abiding by the same data-security standards they enforce internally. (Both the Target and Home Depot breaches occurred via such third-party networks.) For example, the credit-card-issuing banks are suing Target to recoup some of their losses from last year's breach by claiming the retailer didn't apply even the minimum level of data security measures to its networks. What can you and I do to protect ourselves from the Internet's nogoodniks? Be vigilant: Watch your monthly statements, be judicious in choosing the organizations you transact with online, and make sure all your sensitive data is encrypted, no matter where it's stored. Also, keeping your fingers crossed couldn't hurt. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ |

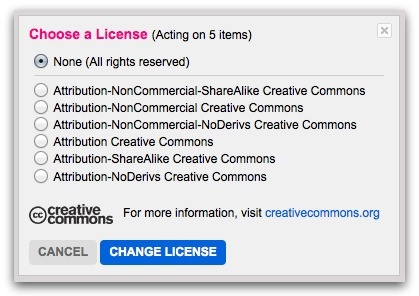

Yahoo cashes in on your cute, royalty-free Flickr images

Millions of people have uploaded billions of images to Yahoo's Flickr image-sharing service. Not many of the uploaders expect any payment from people who download or otherwise use their images. In a December 10, 2014, post on the Sophos Naked Security blog, Lisa Vaas explains that Yahoo is planning to make canvas prints from 50 million Flickr images that have Creative Commons licenses. The prints will be sold for up to $49 each, according to Vaas. The company will also use images for the prints whose creators have retained the licensing rights to; these people will receive a 51-percent share of the sales proceeds. The CC licensees are out of luck -- and there's nothing illegal about it. Not all the people whose CC-licensed images will be used object to the lack of any payment, however. Many are satisfied with the extra exposure the prints will afford them. If you're a Flickr user who would like to retain the rights to your images, you can change the license type by opening your Albums and choosing "Batch edit > Change licensing." Your licensing options are shown in the image above. As Vaas points out, for people who've uploaded thousands of CC-licensed images to the service, there's no practical way to opt out of Yahoo's unfettered reuse of the pictures. The lesson is to be careful about which Internet services you trust with your data. Once a file is in the cloud, you've ceded a goodly amount of control over it, one way or the other. Could external hard drives be making a comeback? Nah, but maybe a new kind of cloud-storage service is needed -- one such as SpiderOak that lets you encrypt your data before you upload it so that only you can decrypt it. |