Menu

Simple, free ways to lock down your private data |

Some politicians think of themselves as shamans or wizards. Their laws are spells or incantations with supernatural power. They pass some regulation they believe will magically reverse the laws of nature.

To which nature replies, "Hah!" These rulemakers think they can build a back door into data encryption systems that will allow access to the data by law enforcement and spy agencies, while keeping everyone else out. The first problem is obvious: the bad guys can find and use any back door inserted for law enforcement to use surreptitiously. Here's another problem: Strong encryption systems without back doors have been in use for years and will continue to be in use -- by good guys and bad guys alike. There isn't a thing anyone can do about it -- at least not until the first quantum computers arrive that are powerful enough to crack strong encryption. The strong-encryption cat's out of the bag, Pandora's box is wide open, the genie's out of the bottle -- any way you want to put it, everyone has access to encryption that can't be cracked. No laws, regulations, or prohibitions will make these encryption systems unavailable. (Security expert Bruce Schneier explains why strong encryption is the only encryption that matters.) Opera browser gives you instant VPN and built-in ad blocking For some reason, virtual private networks are more popular than ever. I wonder why that might be? It couldn't have anything to do with the topic of last week's Weekly, could it? Plain and simple, VPNs prevent your internet service provider from tracking you. Even after you've blocked ads and trackers, your ISP knows your entire browsing history. That includes the sites you visit when you're in your browser's "privacy" mode. This feature keeps your browsing history off your local machine or device only and has no effect on the tracking being done by third parties, including your ISP. Back in November I wrote about virtual private networks and recommended against free VPN, but that was before the Opera browser added a VPN. (Technically, Opera had VPN before I wrote that, but I just learned about the feature recently -- oops!) To activate Opera's VPN, open the Preferences window, choose "Privacy & security" in the left pane, and check "Enable VPN" under VPN on the right side. While you're in Opera's preferences, check the option to block ads. You might consider enabling the "do not track" feature, which sends requests not to be tracked to all the sites you open. The Electronic Frontier Foundation points out that "do not track" requests may not always be honored. The EFF goes with a two-pronged approach:

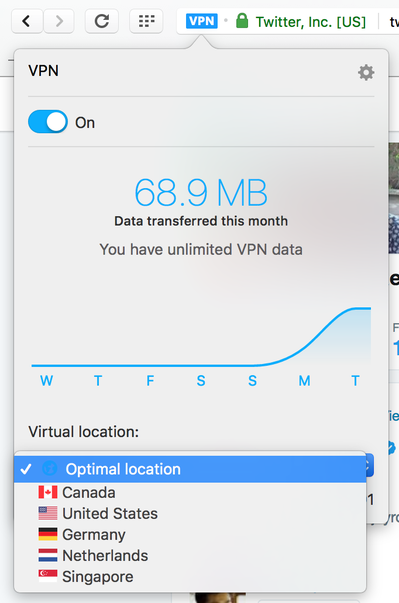

By the way, the article from last November also described encrypted email services and sites offering encrypted online storage, which might come in handy as well. After you enable Opera's VPN, a blue "VPN" icon appears to the left of the address bar, as shown in the image above. Select it to view the amount of data transfered via VPN in the current month, and your IP address. Choose the drop-down menu at the bottom of the window to select one of five countries to host your VPN connection: Canada, U.S., Germany, Netherlands, or Singapore. The default setting is "Optimal location." Where VPNs come up (slightly) short VPNs aren't a privacy cure-all. Wired's Klint Finley describes some of the shortcomings of VPNs, such as having to trust your VPN service. In Opera's case, the VPN provider is a Canadian company named SurfEasy, about which I know nothing. If you prefer the do-it-yourself approach to VPNs, FreeCodeCamp's Quincy Larson explains how to set up a VPN in 10 minutes for free. Larson recommends the EFF's HTTPS Everywhere browser extension, which ensures that your browser uses secure HTTPS connections to sites whenever they are available. HTTPS Everywhere has nothing to do with VPNs, though. VPNs work by creating a secure "tunnel" for all of your internet communications to travel through. Larson discusses a handful of VPN services and lists those recommended by some of his Twitter followers. I continue to recommend SecurityKISS, an Irish-based VPN service that offers a free plan allowing up to 300MB of data transfers per day. An economy plan costs 2.99 euros a month (about $3.24) or 23.90 euros a year (about $25.86); it has a data limit of 20GB per year. ------------------------------------------------------ Linkapalooza State houses to the rescue? It's not much privacy protection, but at this point we'll take what we can get. The New York Times' Conor Dougherty reports that Illinois is one of several states considering laws intended to limit access to consumers' private information. The right-to-know regulations would require that internet services such as Google and Facebook would have to disclose what information they collect about people, and who they're sharing the information with. The law affects only residents of Illinois, but privacy advocates hope it will serve as a model for other states to adopt to protect their residents. Dougherty points out that web services are in full lobby against the Illinois proposal and similar ones in other states. Illinois is home to the Biometric Information Privacy Act that restricts the collection of voice recordings, fingerprints, facial scans, and other biometric data. A Chicago-based class-action law firm named Edelson PC has made a name for itself in bringing privacy actions against web services based on the law. Now firm lawyers have helped form the Digital Privacy Alliance to fight for consumer privacy rights "in Illinois and elsewhere," according to Dougherty. Not all the clueless legislators are in D.C. California Assemblymember Ed Chau may have had the best of intentions when he proposed a bill making it illegal to post on the internet "a false or deceptive statement" about a candidate for office, or attempting to influence an election. As the EFF's Dave Maass writes, the law would have made it a crime "to be wrong on the internet if it could impact an election." The EFF was one of several privacy advocates to point out, quickly and vehemently, that the law was unconstitutional on its face. Assemblymember Chau and his colleagues apparently got the message: the bill was pulled and "will not be heard in committee today." Apart from the hubris of a politician making lying illegal, the law ignores the fact that without mud-slinging, there would be no politics. Wondering what you can do to help? A group of resistors (not the electronic kind) have created the Indivisible Guide that is an attempt to obstruct the current regime as effectively as the Tea Party bolloxed things up for the Obama Administration. The self-described "former progressive congressional staffers" behind the guide offer tips on the most-effective ways to influence Congress to "fight the Trump agenda." The guide includes a way to search by ZIP code for local resistance groups you can contact or join. When I entered a Sonoma County ZIP code, links appeared to five groups within 20 miles, complete with email, Facebook, and Twitter contacts (when available). Information is also provided for registering a group, hosting a meeting, or planning an action. |