Menu

Trading privacy for the public good

The Internet and privacy are incompatible. Networks are all about identifying and authenticating yourself, otherwise anyone could steal your identity. Think of privacy as the Internet's ante: It's what you pay to get in the game.

Here are the trillion-dollar questions: How much of our privacy are we willing to give up? Who are we giving it up to? And how do they intend to use our data? If they're using it to help themselves, that's one thing. If they're using it to help everyone, that's another.

There's no question that people are concerned about the Internet invading their privacy. A survey released on November 12, 2014, by the Pew Research Center found that 91 percent of respondents in the U.S. agree or strongly agree that the collection of their personal information is beyond their control. Yet 55 percent of us agree or strongly agree that we would give up some personal information in exchange for use of a service.

According to the Pew study, 80 percent of Americans agree or strongly agree that we should be concerned about the government monitoring our phone and Internet use, 65 percent believe the government should regulate online advertisers, and 34 percent think our online activities should be monitored for the good of society. That pretty much covers the political spectrum.

Information about us is being collected at an ever-accelerating rate. The Internet of Things and smart devices in general put us under the microscope like never before. On the positive side, big data offers researchers an invaluable pool of information to be poked and prodded for keys to solving the world's problems. The catch is, who do we trust to protect our data and ensure it's never used against our best interests? And do we require informed consent to the collection and use of our personal data? That certainly would limit the data's value from an intelligence and law-enforcement perspective, not to mention increasing the cost of collecting it.

(Realistically, the NSA and other information-gathering groups -- legitimate and illegitimate -- can likely access just about any resource on the Internet without being detected, so they aren't likely to be deterred by a government regulation prohibiting or restricting their activities.)

The promise of data analysis to promote the public welfare

Nothing could be better for the public than spotting, eradicating, and preventing deadly diseases and other threats to health and safety, but ownership of your health information remains unsettled. That was a principal subject of discussion at the 8th annual Body Computing Conference held at the University of Southern California in October 2014. InformationWeek's Jeff Bertolucci reported on the conference in an October 6, 2014, article. One of the biggest complications is the need to comply with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations for protecting personal health information.

In a November 6, 2014, article, Wired's Beth Seidenberg, M.D., makes the case for sharing "de-identified" health information for the sake of medical advancement. To Seidenberg, the data's benefits to scientists far outweigh the privacy risk to consumers. Note that Seidenberg is a general partner with the investment firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, emphasizing life sciences and digital health investing, which may explain her bullishness on the subject.

Apart from the author's potential bias, there's another problem with her proposition: "De-identifying" any information is not only difficult, it may be impossible. In an O'Reilly Radar post from May 2011, Pete Warden explains "Why you can't really anonymize your data." (Here's where I have to add the obligatory note that I'm not that "O'Reilly.")

What your wearable can share about you

When it comes to the health information we collect about ourselves, researchers at the University of California at San Diego report that people are willing to donate to scientists the personal health information their wearable devices collect. However, 57 percent of the device users said they would do so only if their anonymity is assured. The study, Personal Data for the Public Good, was published in March 2014 by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

There's a tremendous amount of personal health information being collected outside the traditional healthcare-provider network, much of it by wearable devices such as FitBit, Jawbone, and Microsoft's Band. Time Magazine's Bryan Walsh describes several of these health-tracking products in a November 14, 2014, article.

One of the tenets of computer science is, "Garbage In, Garbage Out." Many health researchers are hesitant to trust the reliability of the data being collected by wearable devices. The UC-San Diego scientists believe the trustworthiness of the data will improve as the industry matures and standards are developed.

Now FitBit data is being introduced in a personal-injury lawsuit as evidence of the plaintiff's loss of physical ability. Forbes' Parmy Olson reports in a November 16, 2014, article that lawyers for a woman in Canada who was injured in a car accident will introduce her FitBit data to prove diminished capacity; the woman worked as a personal trainer prior to the accident. The accident occurred four years ago, which is long before the FitBit was introduced. The woman's lawyers hope to show via the current FitBit data that her physical abilities are now far below those of a typical personal trainer.

A growing number of people share their health information on sites such as PatientsLikeMe and Crohnology. This week, PatientsLikeMe announced a promotion entitled 24 Days of Giving that's intended to encourage people with chronic medical conditions to share their symptoms, treatments, and quality of life on the site for their benefit and the benefit of others.

PatientsLikeMe is up front about making its money by selling the "de-identified" information you share on the site with its partners, whose "products may include drugs, devices, equipment, insurance or medical services," according to the service's FAQ.

"Share and share alike" was never more appropriate.

Find out what Google knows about you

If you're curious about what kind of information Internet services are collecting about you, Google has a setting that will fill you in. Sign into your account, click your picture in the top-right corner, and choose Account. Select "Account history" and then click "Manage history" in any of the four categories: "Things you search for," "Places you've been," "Your YouTube searches," and "Things you've watched on YouTube."

You can pause the history tracking in any of these categories, or enable tracking if it is currently disabled. You can also edit your settings for Google+, shared endorsements, search settings, and ads.

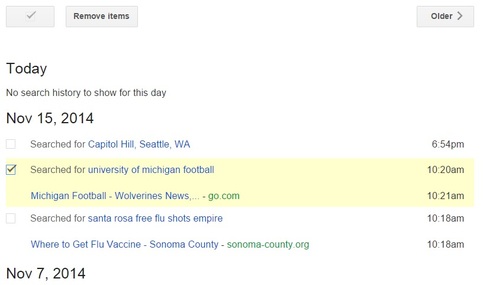

The Google Search History page graphs your hourly, daily, and monthly search activity, as well as your top clicks, top queries, and top sites (click "Show more trends" to view all available graphs). Your daily search activity is listed below the graphs; to remove items from your search history, check their boxes on the left and click the "Remove items" button. To wipe your history clean, check the box to the left of the button and then click "Remove items." (The screen is shown at the top of this post.)

One option in your search settings you may want to change is private results, which includes your Gmail, Google+, and Google Calendar content in search results. The option is enabled by default. I prefer to search Gmail and other Google services separately rather than mix their search results with Web content, so I disabled this feature. Likewise, I have disabled Google Location History altogether.

To change what you share with Google advertisers, click "Edit settings" next to Ads in the "Related settings" box. The information is taken from you Google profile, but you can opt out of "interest-based" ads in Google products and across the Web.

The many, many ways you can be identified online

Chances are pretty good you know about the tracking cookies Web services use to collect information about you and your online activities. You may even have changed your browser settings to block third-party cookies, as I explained in a post from June 24, 2014, entitled "Browser security settings you gotta change." (It's impractical to block first-party cookies because doing so breaks nearly every site. You can set your browser to delete all cookies when you close the program, but the site keeps a copy of your cookie and reloads it as soon as you return.)

There are many other techniques used by Web trackers to record the details of your Internet life. As part of Google's Chromium Projects, two of the company's researchers, Artur Janc and Michal Zalewski, have compiled a "Technical analysis of client identification mechanisms."

In addition to your standard, everyday HTTP cookie, you got your Flash Local Shared Objects (LSOs) and Silverlight Isolated Storage, HTML5 client-side storage mechanisms, and various forms of browser cache tricks. Then you have your machine and browser fingerprinters, which take a snapshot of your system's unique characteristics and settings. That snapshot is used to " cross-correlate user activity across various browser profiles or private browsing sessions," according to the researchers.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation's Panopticlick demonstrates how easy it is to follow you around the Internet based solely on such machine profiles. And unlike nearly all cookies, the machine fingerprinters don't need to store an identifier file on your system to track you. Also unlike cookies, there's no way to know when your system is being fingerprinted, nor any reasonable way to prevent the practice.

Is Google too powerful?

One last word on the Internet's 900-gigaton gorilla: In a November 13, 2014, article, Common Dream's Deidre Fulton posits that Google has gotten so powerful politically that regulators and government officials are reluctant to investigate the company's increasingly invasive operations.

According to OpenSecrets.org, Google spent more on lobbying in the first three quarters of 2014 than any other corporation. Google's recent acquisitions include the Skybox service that captures high-definition images and video via satellite; the Nest and Dropcam services that monitor your home; and the Emu service that eavesdrops on and places ads in text messages and online chats.

Much of the information in the article is based on a report published this month by Public Citizen entitled Mission Creep-y: Google Is Quietly Becoming One of the Nation’s Most Powerful Political Forces While Expanding Its Information-Collection Empire (pdf).

Practically speaking, you can't use the Internet without being tracked. Tracking needn't be an altogether bad thing, if the people being tracked had the means to monitor and control the information being gleaned about them. Would you be more willing to let Google and other Web services collect information about you if you knew the collection was serving the public and not just a bunch of Internet billionaires?

Here are the trillion-dollar questions: How much of our privacy are we willing to give up? Who are we giving it up to? And how do they intend to use our data? If they're using it to help themselves, that's one thing. If they're using it to help everyone, that's another.

There's no question that people are concerned about the Internet invading their privacy. A survey released on November 12, 2014, by the Pew Research Center found that 91 percent of respondents in the U.S. agree or strongly agree that the collection of their personal information is beyond their control. Yet 55 percent of us agree or strongly agree that we would give up some personal information in exchange for use of a service.

According to the Pew study, 80 percent of Americans agree or strongly agree that we should be concerned about the government monitoring our phone and Internet use, 65 percent believe the government should regulate online advertisers, and 34 percent think our online activities should be monitored for the good of society. That pretty much covers the political spectrum.

Information about us is being collected at an ever-accelerating rate. The Internet of Things and smart devices in general put us under the microscope like never before. On the positive side, big data offers researchers an invaluable pool of information to be poked and prodded for keys to solving the world's problems. The catch is, who do we trust to protect our data and ensure it's never used against our best interests? And do we require informed consent to the collection and use of our personal data? That certainly would limit the data's value from an intelligence and law-enforcement perspective, not to mention increasing the cost of collecting it.

(Realistically, the NSA and other information-gathering groups -- legitimate and illegitimate -- can likely access just about any resource on the Internet without being detected, so they aren't likely to be deterred by a government regulation prohibiting or restricting their activities.)

The promise of data analysis to promote the public welfare

Nothing could be better for the public than spotting, eradicating, and preventing deadly diseases and other threats to health and safety, but ownership of your health information remains unsettled. That was a principal subject of discussion at the 8th annual Body Computing Conference held at the University of Southern California in October 2014. InformationWeek's Jeff Bertolucci reported on the conference in an October 6, 2014, article. One of the biggest complications is the need to comply with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations for protecting personal health information.

In a November 6, 2014, article, Wired's Beth Seidenberg, M.D., makes the case for sharing "de-identified" health information for the sake of medical advancement. To Seidenberg, the data's benefits to scientists far outweigh the privacy risk to consumers. Note that Seidenberg is a general partner with the investment firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, emphasizing life sciences and digital health investing, which may explain her bullishness on the subject.

Apart from the author's potential bias, there's another problem with her proposition: "De-identifying" any information is not only difficult, it may be impossible. In an O'Reilly Radar post from May 2011, Pete Warden explains "Why you can't really anonymize your data." (Here's where I have to add the obligatory note that I'm not that "O'Reilly.")

What your wearable can share about you

When it comes to the health information we collect about ourselves, researchers at the University of California at San Diego report that people are willing to donate to scientists the personal health information their wearable devices collect. However, 57 percent of the device users said they would do so only if their anonymity is assured. The study, Personal Data for the Public Good, was published in March 2014 by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

There's a tremendous amount of personal health information being collected outside the traditional healthcare-provider network, much of it by wearable devices such as FitBit, Jawbone, and Microsoft's Band. Time Magazine's Bryan Walsh describes several of these health-tracking products in a November 14, 2014, article.

One of the tenets of computer science is, "Garbage In, Garbage Out." Many health researchers are hesitant to trust the reliability of the data being collected by wearable devices. The UC-San Diego scientists believe the trustworthiness of the data will improve as the industry matures and standards are developed.

Now FitBit data is being introduced in a personal-injury lawsuit as evidence of the plaintiff's loss of physical ability. Forbes' Parmy Olson reports in a November 16, 2014, article that lawyers for a woman in Canada who was injured in a car accident will introduce her FitBit data to prove diminished capacity; the woman worked as a personal trainer prior to the accident. The accident occurred four years ago, which is long before the FitBit was introduced. The woman's lawyers hope to show via the current FitBit data that her physical abilities are now far below those of a typical personal trainer.

A growing number of people share their health information on sites such as PatientsLikeMe and Crohnology. This week, PatientsLikeMe announced a promotion entitled 24 Days of Giving that's intended to encourage people with chronic medical conditions to share their symptoms, treatments, and quality of life on the site for their benefit and the benefit of others.

PatientsLikeMe is up front about making its money by selling the "de-identified" information you share on the site with its partners, whose "products may include drugs, devices, equipment, insurance or medical services," according to the service's FAQ.

"Share and share alike" was never more appropriate.

Find out what Google knows about you

If you're curious about what kind of information Internet services are collecting about you, Google has a setting that will fill you in. Sign into your account, click your picture in the top-right corner, and choose Account. Select "Account history" and then click "Manage history" in any of the four categories: "Things you search for," "Places you've been," "Your YouTube searches," and "Things you've watched on YouTube."

You can pause the history tracking in any of these categories, or enable tracking if it is currently disabled. You can also edit your settings for Google+, shared endorsements, search settings, and ads.

The Google Search History page graphs your hourly, daily, and monthly search activity, as well as your top clicks, top queries, and top sites (click "Show more trends" to view all available graphs). Your daily search activity is listed below the graphs; to remove items from your search history, check their boxes on the left and click the "Remove items" button. To wipe your history clean, check the box to the left of the button and then click "Remove items." (The screen is shown at the top of this post.)

One option in your search settings you may want to change is private results, which includes your Gmail, Google+, and Google Calendar content in search results. The option is enabled by default. I prefer to search Gmail and other Google services separately rather than mix their search results with Web content, so I disabled this feature. Likewise, I have disabled Google Location History altogether.

To change what you share with Google advertisers, click "Edit settings" next to Ads in the "Related settings" box. The information is taken from you Google profile, but you can opt out of "interest-based" ads in Google products and across the Web.

The many, many ways you can be identified online

Chances are pretty good you know about the tracking cookies Web services use to collect information about you and your online activities. You may even have changed your browser settings to block third-party cookies, as I explained in a post from June 24, 2014, entitled "Browser security settings you gotta change." (It's impractical to block first-party cookies because doing so breaks nearly every site. You can set your browser to delete all cookies when you close the program, but the site keeps a copy of your cookie and reloads it as soon as you return.)

There are many other techniques used by Web trackers to record the details of your Internet life. As part of Google's Chromium Projects, two of the company's researchers, Artur Janc and Michal Zalewski, have compiled a "Technical analysis of client identification mechanisms."

In addition to your standard, everyday HTTP cookie, you got your Flash Local Shared Objects (LSOs) and Silverlight Isolated Storage, HTML5 client-side storage mechanisms, and various forms of browser cache tricks. Then you have your machine and browser fingerprinters, which take a snapshot of your system's unique characteristics and settings. That snapshot is used to " cross-correlate user activity across various browser profiles or private browsing sessions," according to the researchers.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation's Panopticlick demonstrates how easy it is to follow you around the Internet based solely on such machine profiles. And unlike nearly all cookies, the machine fingerprinters don't need to store an identifier file on your system to track you. Also unlike cookies, there's no way to know when your system is being fingerprinted, nor any reasonable way to prevent the practice.

Is Google too powerful?

One last word on the Internet's 900-gigaton gorilla: In a November 13, 2014, article, Common Dream's Deidre Fulton posits that Google has gotten so powerful politically that regulators and government officials are reluctant to investigate the company's increasingly invasive operations.

According to OpenSecrets.org, Google spent more on lobbying in the first three quarters of 2014 than any other corporation. Google's recent acquisitions include the Skybox service that captures high-definition images and video via satellite; the Nest and Dropcam services that monitor your home; and the Emu service that eavesdrops on and places ads in text messages and online chats.

Much of the information in the article is based on a report published this month by Public Citizen entitled Mission Creep-y: Google Is Quietly Becoming One of the Nation’s Most Powerful Political Forces While Expanding Its Information-Collection Empire (pdf).

Practically speaking, you can't use the Internet without being tracked. Tracking needn't be an altogether bad thing, if the people being tracked had the means to monitor and control the information being gleaned about them. Would you be more willing to let Google and other Web services collect information about you if you knew the collection was serving the public and not just a bunch of Internet billionaires?